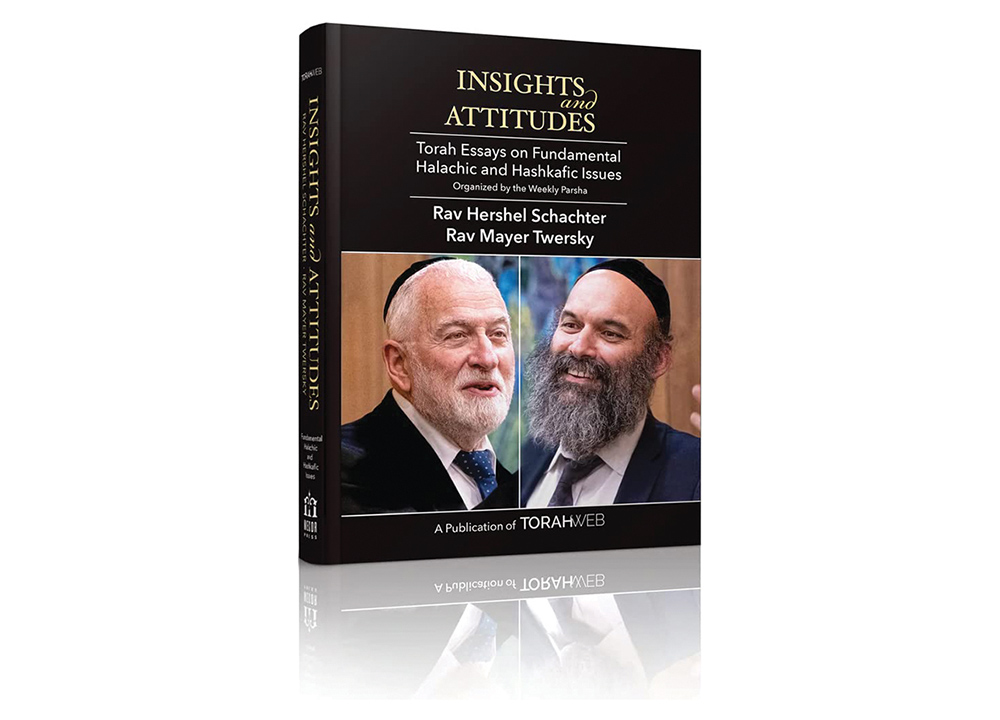

Editor’s note: This series is reprinted with permission from “Insights and Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains multiple articles—organized by parsha—by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

The pasuk in parshas Shoftim uses three different phrases to describe a disagreement about halacha בין דם לדם בין דין לדין ובין נגע לנגע (Devarim 17:8). The Vilna Gaon is quoted in the sefer “Aderes Eliyahu,” as having commented that this language indicates that all the dinim of the Torah are classified into three distinct categories: issur veheter, dinei mamonos and tuma vetahara. The parsha states that if in any one of these three areas there is a machlokes among the chachamim in town which is ripping apart the community, the issue must be presented to the Sanhedrin in Yerushalayim, which should give the pesak that will be binding on all of klal Yisrael. The implication is that were it not for the fact that the machlokes among the rabbanim is causing friction and ripping apart the community, each group would follow its own posek.

The Tosefta (Sanhedrin 7:5) tells us that all the laws of the Torah are interconnected and fall into one big pattern, comprising one big mosaic. The Gemara will, therefore, often learn out the details of one mitzvah from another mitzvah. Nonetheless, the Gemara does put limitations upon this concept of all of Torah fitting into a single pattern. The Gemara says that issur veheter can neither be learned out from tuma vetahara (Yevamos 103b) nor from dinei mamonos (Brachos 19b). These sources seem to be implying that each one of the three areas of halacha makes up its own pattern. All of dinei mamonos fit into one pattern; all of the laws of issur veheter fall into a separate pattern, etc (see Sefer Eretz HaTzvi, siman 2).

When we are in doubt as to what the facts of a case are, the halacha has a different way of resolving the safek depending on which category of dinim the case at hand belongs to. Regarding issur veheter, we assume that any safek regarding a דין מן התורה must be resolved lechumra. However, when we have a safek in the area of dinei mamonos, the pesak will be in favor of the muchzak (possession is nine-tenths of the law), which is lekula. Finally, when the safek is in the area of tuma vetahara, whether the pesak will be lehachmir or lahakel will depend on the location where the safek arose—in a reshus hayachid or in a reshus harabim.

In addition to these three areas of halacha, the Gemara tells us that there are another three areas that are treated differently. With respect to dinei nefashos, the Torah tells us העדה והצילו (Bamidbar 35:25), i.e., we should always bend over backwards to try to acquit the person being judged, and this applies, even with respect to the way we darshan the halachos, by reading in between the lines (Sanhedrin 69a). In the area of avodah zara, the Torah tells us “שַׁקֵּ֧ץ תְּשַׁקְּצֶ֛נּוּ” (Devarim 7:26) etc., which implies that we should always bend over backwards to go lechumra when darshening the pesukim, and in the area of Kodshim, the Gemara (Zevachim 49-50) discusses—at length—the fact that the מדות שהתורה נדרשת בהן apply differently to Kodshim from how they apply to the rest of the Torah regarding למד מן הלמד (learning out C from B, where B itself was derived from A).

Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi edited the mishnayos and divided everything into six sections. The sedarim of Nezikin, Kodshim and Taharos constitute three separate areas of halacha.

Some are only careful in observing those mitzvos which are בין אדם למקום and not that meticulous in Nezikin (בין אדם לחבירו). Others are only extremely careful in observing those mitzvos which are בין אדם לחבירו, but are not that meticulous in observing those mitzvos in the area of issur veheter (בין אדם למקום). An Orthodox Jew is one who is equally meticulous in all areas.

It is quoted in the name of the Vilna Gaon that many divide all mitzvos into two categories: בין אדם למקום and בין אדם לחבירו. In reality, there is a third category: בין אדם לעצמו. We have the mitzvah of vehalachta bidrachav—to preserve the tzelem Elokim that was implanted within us at birth by developing our middos. The Gemara (Bava Kamma 30a) tells us that one who wishes to become a chasid should be meticulous in three areas of halacha—avos, nezikin and brachos. These three represent the three areas of

mitzvos—אדם לחבירו ,בין אדם לעצמו בין and בין אדם למקום.

Unfortunately, many people are only selectively observant. Listed among the various mumin (wounds or blemishes) that invalidate a Kohen from being makriv korbanos in the Beis Hamikdash is sarua, one whose limbs are not symmetrical (e.g., one arm is noticeably longer than the other; one eye is noticeably larger than the other). I remember Rav Nisson Alpert’s hesped at the funeral of HaGaon Rav Moshe Feinstein, zt”l, wherein he mentioned that he met many gedolim in his lifetime who he felt suffered, in a certain sense, from the mum of sarua. Some were very meticulous in one area of halacha, but not to the same extent in other areas. And some were especially strong in learning in one area of Torah (pesak halacha, Kodshim, Nashim and Nezikin, etc.) but not equally as strong in all other areas of Torah. The one and only gadol baTorah he knew who seemed to be equally strong in all areas of Torah and equally meticulous in all areas of mitzvos at the same time was his rebbi—HaGaon Rav Moshe Feinstein.

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been Rosh Kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes, and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish Law.