Annually, over Pesach—our zeman cheiruteinu—we relive our emancipation from Egyptian slavery. Arguably, we enjoy greater liberty than any previous generation. Over the past few centuries, society has reinvented itself, progressing toward greater freedom. The emergence of democracy eliminated ancient and abusive forms of government, which had suppressed human imagination and crushed individual liberty. Religious liberty followed soon thereafter. Jews—who had been religiously persecuted for close to 1500 years—were the primary beneficiaries of the freedom of religious worship.

Subsequently, political liberty yielded economic liberty, as capitalism began to inspire the human imagination and incentivize innovation and discovery. The industrial revolution dramatically improved living conditions and human welfare.

More recently, the technological revolution has granted additional layers of liberty. First, mechanization liberated us from the heavy toll of household chores, freeing up time for personal recreation and professional pursuits. Freedom from domestic duties was especially liberating for women, who had previously borne the brunt of these responsibilities.

Even more recently, the internet revolution has accorded freedom of information. Knowledge is power, and by affording universal access to knowledge, the internet has empowered us to be less dependent upon centralized outlets of information. We can now select where and how we access information. Over the past 400 years, the world has experienced a dizzying whirlwind which has remodeled a restrictive society into a world of freedom and personal autonomy.

Pesach is perfectly suited for savoring the freedom we, sometimes, take for granted. Our exodus from Egypt launched the great march of human liberty. Hashem intervened in history, wiping out a tyrannical regime which had abused human liberty and had debased human dignity. As His children, we were challenged to craft a society which wasn’t based on power and might, but upon moral conscience and the will of a Higher being. If Hashem had scrutinized our behavior and held us accountable, perhaps, brute force and aggression wouldn’t have been necessary to maintain order and public welfare.

It took centuries for humanity to fully incorporate the freedoms of Pesach, but, thankfully, most of the modern world values personal liberty and the construction of societies is predicated upon personal autonomy and human dignity. In many ways, the modern world embodies the revolution of Pesach.

20th Century and 21st Century

The 20th century could be termed “the great century of democracy,” as the free world triumphed over fascism and communism. However, these euphoric victories have provided a false sense of security about the stability and durability of democracy. The 21st century has demonstrated just how flimsy democracy can be. Democracies must be built upon public consensus, but common consent is becoming harder and harder to maintain. Without common consensus, politics and society become polarized and democracy begins to wobble. Sadly, we are experiencing these political tremors in Israel, and they have ruptured our national unity. We pray that democracies will prove resilient to the external pressures and internal tensions they currently face.

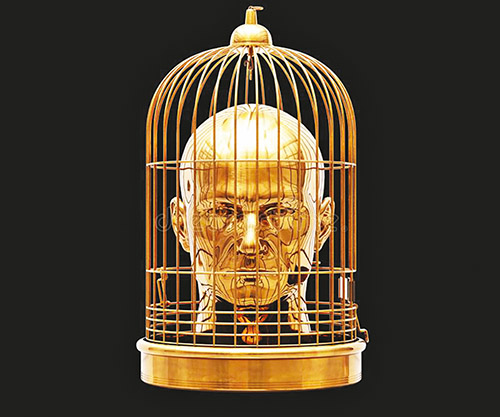

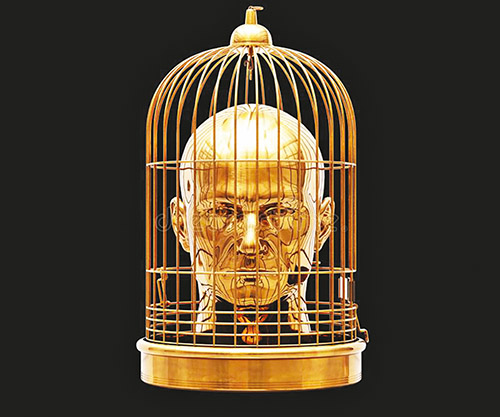

The Trap of Freedom

Just as Pesach is a time to savor human freedom, it is also a moment to scrutinize its latent dangers. Every great revolution masks hazardous threats, which advance under the cover of that revolution. We become so enamored with revolutionary ideas and their intoxicating promises, that we ignore dangers which lurk quietly in ambush. Freedom is no different, and the almost unlimited freedom of our world presents moral and religious challenges. On Pesach, an unconditional celebration of freedom would be partial and dishonest if we weren’t also sensitive to its moral challenges. The religious dangers of unlimited freedom are obvious. Religious experience is based on submitting to the higher will of Hashem and veneration of freedom as the paramount value can create dissonance between societal values and religious mentality. What are the moral challenges of unlimited freedom?

Is It Real?

The internet has liberated us from information control—empowering us to access knowledge independently—thereby, shattering our dependency upon governments and agenda-driven news outlets. Information is flowing more freely than ever. It is also overflowing and swamping us.

The information flow has been decentralized and deregulated, but also has been warped. There is too much information available, and it is too easily manipulated under the cover of anonymity which the internet provides. Unable to separate fact from fiction, we are plagued by fake news. Confused about the difference between truth and falsehood, we doubt the veracity of everything … including ourselves.

This doubt is starting to bleed into our personal lives. The modern swirl has produced a new psychological disorder called “impostor syndrome,” in which we express persistent self-doubt about our real accomplishments: perhaps, they are fake or impostor accomplishments. Perhaps, at some point, the deceit will be discovered, and we will be exposed as a sham. In a world in which truth is elusive and the boundaries between true and false are distorted, we ourselves become lost in doubt and uncertainty. Without certainty, there is no passion or conviction. We fall into apathy and indifference. If everything is unclear, nothing matters.

Dependence Upon Dependencies

By providing independent access to information, the internet has also released us from natural and healthy dependencies. Before Google, we were forced to ask older people—usually parents—for help and guidance about life. Medical questions, fixit questions and general inquiries about life were all directed at those with greater knowledge and more experience. This dependency bolstered healthy parent-child relationships: parents felt valued because their experience and wisdom was needed; while children naturally deferred to parents who possessed important information. Today, it is far more common for parents to ask children for assistance in learning new technologies. When children have little need for parents, the parent-child relationship falters. Google has upended the natural respect once felt for elders.

Similarly—prior to GPS and Waze—we were forced to speak with strangers to ask for directions. Speaking with strangers develops our communicative skills and teaches us politeness. Travel was a perfect opportunity to engage with people different from us. We now travel in hushed silence, cut off from valuable opportunities to communicate with others. Cell phones don’t exactly help our interpersonal or communicative skills either.

Dependencies on others for information or guidance is a vital aspect of emotional well-being and of healthy relationships, but the internet is slowly killing them off, one by one. We are freer than ever to gather information, but we live alone in quiet prisons, trapped in front of screens.

Searching for Identity

Previous societies were built upon rigid hierarchies. Political, social, racial and economic hierarchies were rigidly enforced, and society offered little opportunity for upward mobility. These hierarchies were oppressive, but they also provided clear and unmistakable value systems upon which people built their identity. The church may have abused its power, but it presented clear values about religion and identity. Kings may have bled their citizens dry, but they also symbolized—often hypocritically—a set of national values and ideals that were worth dying for. A world of absolute hierarchies offered absolutes. People were born into a fixed identity, which provided rugged scaffolding for human experience.

The abolition of hierarchies and the expansion of freedom have created a crisis of identity. In our world, the only absolute value is freedom from any constraint. Every other value is “up for grabs” and it becomes difficult to craft identity. We begin to ask ourselves, “Whom am I?” If religion, morality, nationality, race or even gender aren’t assumed—and there are no longer any objectives or absolutes—identity becomes quicksand. Unlimited freedom has led to a crisis of identity.

Make no mistake… religious people are prime beneficiaries of the march of freedom. Freedom is built upon a religious notion that man is Hashem’s exquisite creature, and his dignity and autonomy must be preserved. However, too much of anything is dangerous, and no human convention is perfect. Take the time to carefully gauge the perils of freedom.

The writer is a rabbi at Yeshivat Har Etzion/Gush, a hesder yeshiva. He has semicha and a BA in computer science from Yeshiva University as well as a masters degree in English literature from the City University of New York.