On Megillah 7a, Rav Yehuda cites Shmuel that the Book of Esther doesn’t render one’s hands ritually impure. Biblical books generally render one’s hands impure, as a rabbinic decree. People would otherwise store holy books with teruma, holy food, which could cause mice to eat the scrolls. Alternatively, this is a protective measure so that people would respect the scrolls and not touch them with bare hands. Thus, rendering hands impure is related to whether a book has sanctity, and should be considered part of the Biblical canon.

The Talmudic Narrator contrasts Shmuel’s position with a “known” statement of Shmuel, that Esther was composed with Divine Inspiration (ruach hakodesh). It harmonizes, explaining that Shmuel’s position is that the Divine Inspiration is that it be read, not that it be written down. (See Tosafot ad loc. for some of the difficulties with this approach.) Where is Shmuel’s known statement? Sometimes both Amoraim (Brachot 9a) and the Talmudic Narrator extrapolate what someone’s opinion must be rather than relying upon a direct report. See Chullin 94a: וְהָא דִּשְׁמוּאֵל לָאו בְּפֵרוּשׁ אִתְּמַר אֶלָּא מִכְּלָלָא אִתְּמַר.

In our sugya they derive Shmuel’s position from his response to a brayta, in which several Tannaim give Scriptural proof that Esther was Divinely inspired. Each Tanna pointed to a fact mentioned in the Megillah that a human author couldn’t have known. For instance, a human author wouldn’t know what “Haman said in his heart” (Esther 6:6). Rav Yehuda (b. Yechezkel, second-generation Amora, Pumbedita academy) cites his teacher Shmuel (first-generation Amora), who responds, “Had I been there, I would have given a superior derasha, from קִיְּמוּ וְקִבְּלוּ” (Esther 9:27). Shmuel interprets the duplicative language to mean קִיְּמוּ לְמַעְלָה מַה שֶּׁקִּיבְּלוּ לְמַטָּה, they confirmed in Heaven what was accepted on Earth. Some explain that only a Divinely inspired author would know what they confirmed Above. I’d suggest that this is a direct derasha to the Divine approval of the ordinances and therefore the canonicity of the book. (See also Esther 9:32, קִיַּ֕ם … וְנִכְתָּ֖ב בַּסֵּֽפֶר, about confirming and writing.) The Narrator assumes that Shmuel wouldn’t suggest an interpretation for something he doesn’t personally hold.

Rava (fourth-generation, Pumbedita) endorses Shmuel’s derasha, saying that each Tannaitic proof has possible refutation (e.g., logical inference of Haman’s internal thought process), while Shmuel’s proof has no refutation (because it references happenings in Heaven; or as a direct derasha for canonicity).

Tosafot (ad loc.) are troubled by Rava’s endorsement. How could Rava say there’s no refutation, when elsewhere Rava interprets Shmuel’s same verse differently? Namely, in Shabbat 88a, Rava responds to an idea that the original acceptance of the Torah was coerced and nonbinding. He says that regardless, the Jews reaccepted the Torah willingly in Achashverosh’s days. קִיְּמוּ וְקִבְּלוּ means קיימו מה שקבלו כבר, they confirmed then what they had accepted earlier at Har Sinai. (He channels this derasha from a brayta, Shavuot 39a, where its intent differs slightly: that innovated future commandments such as reading the Megillah were also part of the oath in Arvot Moav.)

Tosafot (in Shabbat) suggest we emend one of the two conflicting “Rava” (fourth generation) to “Rabba” (third generation). Shabbat 88a is viable for emendation (though I find no manuscript support), as he responds to Rav Acha b. Yaakov, a third-generation Amora. However, I think it less possible in our sugya in Megillah. Consider that Ravina I (fifth generation), who is Rava’s student, reacts to Rava’s analysis and endorsement of Shmuel with the folk-expression, “one sharp pepper is better than a basketful of pumpkins.” I’d like Ravina to comment on Rava’s statement. However, note that Rabba (b. Nachmani, third generation, Pumbedita) is Rav Yehuda’s student, so that’s also a good connection.

Our sugya is part of a triplet of sugyot with identical structure. In Chagiga 10a, several Tannaim offer Scriptural bases for a Sage nullifying vows, Rav Yehuda cites Shmuel that “Had I been there, I would have proffered the following derasha,” Rava endorses Shmuel’s derasha as unassailable, and a different student of Rava, namely Rav Nachman b. Yitzchak (fourth-generation Pumbedita), makes the pepper/pumpkin statement. In Yoma 85b, the structure and actors are the same, except that the topic is violating Shabbat to save a life, and the one who talks of pepper/pumpkin is given as either Ravina I or Rav Nachman b. Yitzchak. If we were to emend Rava to Rabba, we’d need to emend three sugyot. Most manuscripts have Rava throughout. An exception is Yoma in Munich 95, which has Rabba, but has Rava in Chagiga/Megillah, and these sugyot must travel together.

Another possibility is this. The Talmudic Narrator is concerned with creating a comprehensive system of derash, in which the mapping between Biblical phrases and Biblical laws is bijective: each law is derived from only one phrase, and each phrase produces only one law. In Sanhedrin 34a, Rabbi Yochanan asserts that one explanation derived from two different verses only counts once, as one derivation must be in error. Abaye explains that while a single verse can be interpreted to produce multiple laws, a single law cannot be derived from multiple verses. (Amusingly, the Gemara cites Abaye and Tanna devei Rabbi Yishmael, who derive the principle from multiple verses.) Rava might agree with Rabbi Yochanan (whom he often channels and expands) and Abaye (his Pumbeditan colleague) in Sanhedrin 34a, and will have two similar derashot from a single verse.

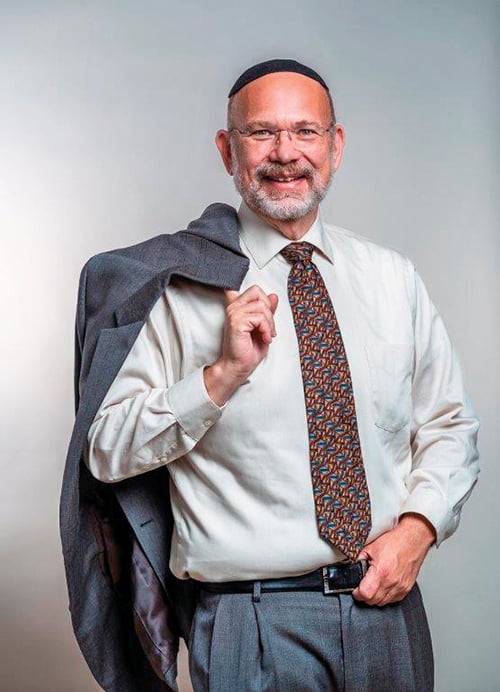

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.