We continue our series on Simon and Garfunkel and great New York cancer scientists/researchers with one who had perhaps one of the most important impacts on cancer-related health in history. The song “The Boxer” starts with the line “I am just a poor boy, though my story’s seldom told,” but we will tell the story of George Papanicolaou now.

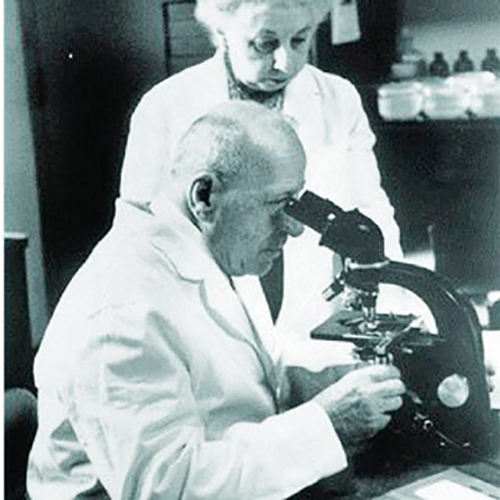

As would be obvious from his name, Papanicolaou was of Greek origin, born in Kymi, Greece, in 1883 to a physician father. He attended the University of Athens where he obtained his MD degree and subsequently studied at several German universities, obtaining a PhD in zoology from the University of Munich in 1910. He returned to Greece, where he married Andromachi Mavrogeni; she became both his research assistant as well as a study subject. By 1913, he traveled to New York City where he joined the pathology department at New York Hospital and Cornell Medical College, and where he worked for the next several decades.

Papanicolaou started off by studying the changes that occurred during the menstrual cycle in the reproductive tract of the guinea pig. He observed that the changes that naturally occur in the uterus itself were also reflected in the vaginal lining or mucosa. He devised a technique of taking vaginal smears from the guinea pig for microscopic examination in 1917, which later became known as the Papanicolaou technique.

He then had the idea of trying this out in humans. Luckily for him, his wife was working as an unpaid lab tech in his lab and was willing to provide samples. Believe it or not, she provided daily vaginal smears for 21 years, and prepared them herself. A woman of valor, who can find?

In 1920, Papanicolaou realized that he could distinguish malignant cells from normal cells on cervical smears. This led to a systematic study in 1925 of normal volunteers together with pregnant patients in which cervical cytologic smears were collected routinely. On one of the smears from one of the patients, he clearly observed cancer cells.

Papanicolaou presented his cytologic low-cost test for the early detection of cervical cancer in 1928 at a medical conference in Michigan. His presentation was met with skepticism and basically ignored. It was not actually formally published in a medical journal until 1941 when it appeared in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. This was followed two years later by a monograph that contained data on 3,000 smears and established the validity and utility of the technique.

The use of the Pap test for screening was widely introduced after 1945. It should be appreciated that at that time cervical cancer was the leading cause of cancer mortality among women. Following the introduction of screening, not only did cervical cancer mortality decline but the incidence of the disease also declined. This was because the cytologic testing was effective in detecting and diagnosing the precursor lesions of cervical neoplasia and thus the aggressive treatment of cervical disease led to the prevention of cervical cancer.

I gather that Papanicolaou was nominated several times for the Nobel Prize but for various reasons was never awarded it. He and his wife remained at Cornell until 1961 when they moved to the University of Miami. He died in 1962.

As an interesting sidelight, working in parallel to Papanicolaou was a Romanian physician, Aurel Babes, who made similar discoveries of the cytologic diagnosis of cervical cancer, which he published in 1928 in a French journal. His methodology used a platinum loop rather than a cotton swab as was utilized by Papanicolaou. Babes was apparently aware of Papanicolaou’s work, but Papanicolaou was unaware of Babes. Most experts in the field believe that the method devised by Babes would not have lent itself to mass screening. Nonetheless, in Romania, the cervical cytologic test is referred to as the Babes-Papanicolaou smear.

Our Boxer may have started as a poor boy, but he made a monumental impact on the world.

Alfred I. Neugut, MD, PhD, is a medical oncologist and cancer epidemiologist at Columbia University Irving Medical Center/New York Presbyterian and Mailman School of Public Health in New York. Email: ain1@columbia.edu.

This article is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, and does not constitute medical or other professional advice. Always seek the advice of your qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment.