Over the recent Sukkot holiday I read an article titled “Halakhic Issues Related to Synthetic Biology” by Rabbi Dr. Moshe D. Tendler, zt”l, (co-authored with John Loike and Ira Bedzow and published in the most recent issue of Hakirah). Synthetic biology is a new interdisciplinary area involving the application of engineering principles to biology to create new biological structures. This could include the creation of artificial reproductive seed as well as artificially created DNA.

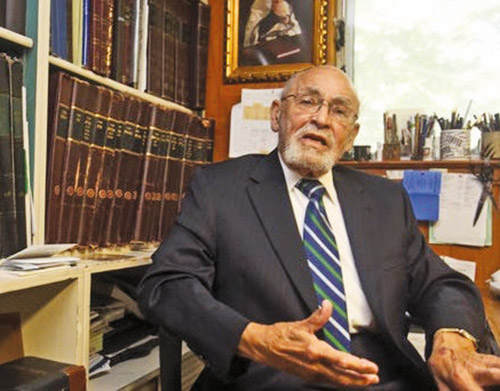

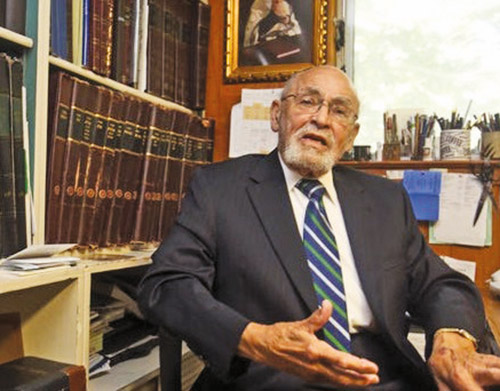

I was not surprised to see Rabbi Tendler write about a cutting-edge medical topic with which few readers are familiar. The fact that he did so at the age of 95 is perhaps notable, but again, not surprising given the author. Since my student days in Yeshiva University, some decades ago, I have been accustomed to hearing or reading the indefatigable Rabbi Tendler address the most current medical topics from an halakhic perspective, often before the Torah world had even known of their existence. These included matters such as brain death, surrogate motherhood, stem cells, cloning, CRISPR and gene editing. I was never disappointed. Yet it is perhaps his final essay topic which best encapsulates his life.

One of the definitions of synthetic biology is that it aims at the design and synthesis of biological components and systems that are not found in the natural world. While the raw materials exist, the final product is unique. Rabbi Tendler’s building blocks were not nucleotide bases (though he was intimately familiar with these), but rather Torah and Madda (worldly knowledge and wisdom). To be sure, both Torah and Madda, and their encounter with each other, have been elemental parts of Jewish life for centuries, but Rabbi Tendler’s unique “synthesis” of the two into a compound structure had simply not previously existed in the natural world. His complete mastery of both science (serving as professor of biology and clinical cancer researcher) and Torah (serving as a Rosh Yeshiva and distinguished community rabbi) at the highest levels, bound in a cohesive double helix through exceptional skills of oratory, wisdom, wit and humor, represented a patentable entity. He wasn’t a representative of Torah u-Madda, he was its very embodiment in the fullest sense of the word. Every molecule and fiber of his being reflected an unbreakable bond between the two.

It has been famously observed of Maimonides, “mi-Moshe ad Moshe lo kam ki-Moshe,” from Moshe (Rabbeinu) to Moshe (ben Maimon) no comparable Moshe had arisen. Comparisons between Moshe ben Maimon and Moshe Tendler are inevitable, for obvious reasons. Yet, there is a fundamental difference between the illustrious Moshes. As is well-known, Maimonides was among the premier Torah sages of history as well as a giant in the field of medicine and science. Yet, there is scant connection between the two fields in his writings. His many medical works, written in Arabic, contain virtually no mention of Torah; and his halakhic works, with the exception of one chapter in the aptly named Sefer Madda, barely contain any medical references. It is the latter Moshe who added the vav ha-hibbur, connecting the worlds of Torah u-Madda, achieving a more complete, unparalleled synthesis, and indissoluble bond between the two, such that they became biologically inseparable.

As a student at Yeshiva University in the 1980s, Rabbi Tendler was my introduction to the world of Torah u-Madda. I am most assuredly not alone. He chartered and defined the field of Jewish bioethics, and through him his students gained access to a previously unknown world of pioneering, state-of-the-art science through the prism of Torah. He designed and taught the first college course in Jewish bioethics, one of the most popular courses of the day. As students in that class, we felt as if we had been gifted a front-row seat at the day’s international medical briefing.

Oscar Wilde quipped that “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery that mediocrity can pay to greatness.” Rabbi Tendler was one of the most imitated personalities at YU. Indeed, many a student could be seen mimicking his distinct voice, hand gestures and delightful witticisms. Yet it is another form of imitation that truly reflects the extent of the flattery bestowed upon him. His methodology of halakhic analysis of medical topics is emulated by all who followed him, myself included. He forever changed the way the Jewish world analyzes and integrates the field of medicine through the lens of Torah.

He was not simply a towering intellectual pontificating over arcane medical halakhic issues of little relevance to the average Jew; he provided practical halakhic guidance in real-life situations, and in real-time, to all those in need on issues relating to abortion, contraception, end of life issues, organ transplantation, the definition of death, and more. No medical topic was outside his bailiwick.

In the second half of the twentieth century, medical school quotas had abated, and doors finally opened for many young Jews, previously denied admission, to attend American medical schools. How could one navigate the seemingly insurmountable halakhic challenges involved in such an endeavor? Rabbi Tendler shepherded generations of future physicians through the halakhic intricacies of medical training. Rabbi Tendler and his dear friend and longtime collaborator, Dr. Fred Rosner, authored a volume entitled Practical Medical Halachah expressly for this purpose. It is no exaggeration to say that Rabbi Tendler’s name was in the Rolodex (or, today, smartphone) of every religious Jewish physician.

Rabbi Tendler’s name appeared on the halakhic advisory board of numerous major Jewish organizations in his day. His presence as a keynote speaker at major Jewish conferences was ubiquitous for decades, especially at the annual conferences of the Association of Orthodox Jewish Scientists, for which he served as the medical posek. His talks were invariably the highlight of the event, with attendees brimming with anticipation of his address. He did not disappoint. His talks were a mix of the latest medicine, the most sophisticated halakha, spiced with his trademark wit, coupled with a healthy dose of unpredictability. Utilizing his transparencies and an overhead projector in the pre-PowerPoint age, he invariably began with a Midrash, often from the week’s Torah reading, which he masterfully and creatively weaved into the topic at hand. As an added bonus, he saved us all the cost of a New England Journal of Medicine subscription by excerpting and synopsizing the articles relevant to halakha and the Jewish community.

Watching him spar with his colleagues on the topic of brain death, bout after bout, was a scintillating experience, an intellectual spectator sport with no equal. Rabbi Tendler was a fierce competitor when he believed truth was at stake in the arena. One could suggest he was striving to achieve “intellectual decapitation,” and first-round knockouts were not uncommon, though some went the full 15 rounds, ending in a split decision.

His expertise on the public stage was not limited to the Jewish world. He served as a medical ethics advisor for innumerable national medical associations and frequently testified before Congress on the ethical implications of medical technologies.

His own contribution to the world of medical halakha was magnified by the advisory and collaborative role he served with his father-in-law, the most prominent Torah figure of the twentieth century, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein zt”l. As Rav Moshe’s interpreter, translator, and transmitter of medical knowledge, Rabbi Tendler played an indispensable and integral role in the medical halakhic decisions rendered by Rav Moshe. In addition to all his other countless contributions, we owe Rabbi Tendler a debt of gratitude for facilitating the halakhic decisions that serve as our unerring guide to this very day. These rulings on topics such as abortion, artificial insemination, end-of-life issues, and the definition of death, laid the foundation upon which today’s medical halakhic landscape stands.

Alas, the article I read just days ago would be the last published by the great Rabbi Tendler in his lifetime. Yet, I am comforted by the fact that his “spiritual stem cells and clones” continue to propagate and will perpetuate his legacy. How nature or nurture will affect the output and productivity of the next generation remains to be seen, but Rabbi Tendler will surely be monitoring the situation from above with great interest. On a personal note, Rabbi Tendler is in no small way responsible for my life’s pursuits. I will remain eternally indebted to him for immeasurably enhancing my life.

Rabbi Edward Reichman, M.D., is a Professor of Emergency Medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. This article is reprinted with permission of TRADITION: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought ( www.TraditionOnline.org )