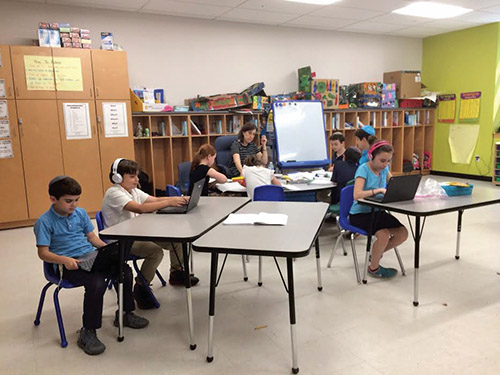

A group of young students at Yeshivat He’Atid sit in a cluster around their teacher as she explains a math lesson to them. Other students in the class sit at their desks with headphones over their ears and their eyes intent on a Chromebook in front of them. Both groups are learning, but in slightly different ways.

He’Atid is not the only school with students working from screens more often than worksheets. With the onset of technology, the methods of teaching have changed teaching immensely since the early days of education. But what sort of impact is it having on students?

At Yavneh Academy, first grade English teacher Donna Domb finds that the technology helps advance young students’ knowledge, and many early childhood students arrive more prepared to meet the demands of first grade. Pre-k students at Yavneh use Lexia, an online literacy improvement program, tailored to students from pre-k to 12th grade. In terms of reading and phonics, Domb says she has seen an improvement in students first entering her classroom, for which she credits Lexia.

Domb has been implementing technology into her curriculum since she first got her Smartboard eight years ago. It allows her to teach the class in a more interactive way than she ever could before.

“I would never want to go back,” she said of trading her Smartboard back in for her old chalkboard. “Teaching was always fun,” said Domb, but now it’s gotten even better.

Domb assigns weekly writing and math homework to her students, which are both assigned and completed online. Domb uses IXL, an online math program that lets students complete as many problems as they want to within a unit. Students can work at their own pace, Domb explained. It’s easier to differentiate instruction to fit the needs of students, and they can move further ahead in their lessons, rather than be limited to the amount of problems on a worksheet.

Rabbi Efrayim Clair, the educational technologist of RYNJ, explained that with the individual assessments most online programs provide, teachers can pinpoint exactly where some students are having trouble grasping a lesson and where others are excelling. Teachers use Chromebooks to provide the lessons online to their students. They also use IXL and other programs like Headsprout, which focuses on reading comprehension skills, explained Clair. Both programs give teachers the data they need to determine how their students are progressing in class. These quick assessments also save the teachers a lot of time, he said.

Having less worksheets to mark gives second grade Yavneh teacher Adrienne Peloso more time for interactive learning. Peloso’s class participates in a “global read aloud” where teachers from different schools Skype each other’s classes and share their classroom experiences.

“It’s like what pen pals used to be,” Peloso said. Students share pictures of winter vacations, read books to each other and do projects together all through Skype. This type of learning motivates students more, Peloso said. “This is their generation’s thing.”

Students in Peloso’s class use online programs like Spelling City to teach kids different grammar and phonics skills, but she does not use the iPad every day, and not all work is done independently by the students. Peloso still gathers the class to the Smartboard in the front of the room to give them their math lesson. This way she can be sure that every student has their eyes on the board and is paying attention.

Teachers like Domb and Peloso, who have so readily adapted to the new age of teaching, still believe in the philosophy of everything in moderation.

While Domb is confident that she incorporates enough writing practice in her daily curriculum for her first graders, Peloso is worried that too much iPad use will hinder students’ writing abilities. She laments not having enough time in her schedule during the day to include more handwriting practice aside from letter-writing exercises the iPads provide.

Both Domb and Peloso worry that the abundance of Smartboards and iPads might cause a lack of socialization among their students.

“At this age they still need a ton of nurturing,” Peloso said. She hopes that online instruction doesn’t replace teacher and student interaction.

That is why administrators like Rav Yair Daar of Yeshivat He’Atid ensure that technology is used in moderation. From as early as kindergarten, students at He’Atid learn to work independently on Chromebooks provided to them by the school. Their online sessions take about 20 minutes a day, while the older children spend about an hour and 15 minutes learning via online instruction. The goal is to foster a more independent learning attitude in their students.

Daar doesn’t fear that students are losing out on any socialization during the school day because of the Chromebooks.

“There’s no difference between spending 20 minutes…listening to a teacher and writing down notes and maybe saying something, or 20 minutes learning online,” he said. Yet, Daar believes that healthy interaction between the teacher and student in a classroom dynamic is too important to let slide with the advent of technology in education. “You have to have that human connection.”

Daar finds that a lot of what makes technology such a fragile topic in terms of education is people’s discomfort with change.

“We have a hard time distinguishing between what makes us uncomfortable and what we think is actually wrong,” he said. “I understand why you would lament losing something important because of technology,” but it’s important to reevaluate what’s important for a more modern school curriculum.

Daar said he hopes society will think about the future of education through a more logical lens; the world changes and we have to keep up, he explained. It’s helpful for teachers adjusting to a more technological curriculum to evaluate what’s worth losing and what’s worth taking on to best benefit their students.

“Education is more than just downloading information into a kid’s brain,” Daar said.

The benefits and potential problems to using technology rest not with the Chromebooks or iPads themselves, but rather with the way they’re being implemented. “It’s not [just about] the technology,” Daar said, “it’s how the technology is used.”

By Elizabeth Zakaim

Elizabeth Zakaim is a rising junior journalism and psychology double major at The College of New Jersey. She is also a summer intern at The Jewish Link. Feel free to email her at zakaime1@tcnj.edu with any questions or comments.