One place I always wanted to take a look at was the ancient Karaite cemetery in the Old City of Hebron (yes, I’m writing about Karaites again). I took a gander at it when I was working on an archaeological dig at Tel Rumeida in 2014. It was overgrown with weeds and locals use part of it as a dump. Looking at the tombstones, I was disappointed to see there was no writing on any of them. I’ve heard that it was the custom among the Karaites to do so.

Archaeology is very much not like how it is portrayed in the movies. It’s more often than not quite unglamorous, mind-numbing and exhausting work. But when you do find something of value, it makes it all worth it. Our toil produced results when we discovered the famed “lamelech” seals from the period of the Tanach.

It is not clear what this signifies. Some have hypothesized that these were actually royal vessels. Others claim that these were vessels housed at various different granaries (warehouses) that were set aside to put in them taxes of wine and grain, etc., for the king’s treasury.

Only four different “lmlch” seal impressions have been uncovered at various archaeological excavations in the Judea area. Four different cities are mentioned (separately, never together): Hebron, Zif, Soko and Memshat (the last one has never been positively identified).

They are dated to the end of the eighth century BCE—the reign of Hezekiah, king of Judah.

I spoke to a local resident (who incidentally caught the archaeology bug while serving in the military) who is an expert on local antiquities and I was made aware of several interesting facts about the area. Said resident archaeologist revealed to me (in response to my query about the lack of tombstone inscriptions) that with much effort he was able to extract some writing from several tombstones.

About the Dig

Back in 2014, The Jewish Press reported that “Emmanuel Eisenberg, representing the Israeli Antiquities Agency, and Dr. David ben Shlomo from Ariel University are jointly heading up renewed digging on Tel Hebron. The areas presently being excavated are labeled ‘plots 52 and 53,’ on the center-south-west section of Tel Hebron. The area is between 5 to 6 dunam, that being some 1.5 acres or 6,000 sq. meters… These renewed excavations are tremendously exciting. The thought of uncovering the original city of David, or even his palace, is mind-boggling. Why so? Hebron is the roots of Judaism, it is the roots of all of monotheism and I also call it the very beginnings of humanity.”

I had left the dig after its first season and was wondering what had become of it. Because of the volatile situation in the area, things have been on the back burner but apparently the site is open for visitors.

What of the Karaite cemetery next to it?

While Karaites undoubtedly maintained a presence there for many generations, very little mention of it is made in the literature describing the site. For instance, Noam Arnon, a leader of the local Jewish community, devotes less than a line to this phenomenon in his history of Hebron.

At some point I began to look for any and all information about Karaite settlement in the area with scant results. We have substantial information on Karaite communities in Jerusalem but almost nothing that I’ve been able to dig up thus far on Hebron. Save for the following references, which in itself present some difficulty.

It appears that in the year 1540 a rabbi by the name of Malkiel Ashkenazi (according to Rabbi Yosef Sambari he was an Ashkenazic native of Safed. According to a Genizah fragment, he also had a brother and a sister who resided in Egypt. According to yet another source he was a native of Anatolia and came from a small town in Turkey) purchased properties in Hebron (which is said to have allegedly contained a large Karaite community) from the local Karaites. All was fine and well until the mid 1800s (according to the testimony given by R. Yehoseph Schwartz, an early Eretz Yisrael geographer) when Karaites from Istanbul, Turkey, attempted to reclaim those properties from its Rabbanite owners. They took their case to the local secular authorities who eventually ruled against them and the properties stayed in Rabbanites hands.

This is all exceedingly strange for several reasons:

If there was ever a substantial Karaite community in Hebron, why don’t we hear anything about them? We have information about their brethren in Jerusalem but why do we know next to nothing about their co-religionists at Hebron?

For close to 350 years the ownership of the former abode of the Karaites in Hebron went unchallenged. What made the Karaites suddenly put forth a claim after so much time had elapsed? More importantly, how accurate is Schwartz’s description of these events? Are there any secondary sources that corroborate this? Any documentation? Luncz calls the story a “legend”…

The eminent Genizah scholar, Simcha Assaf, in his באהלי יעקב repeats the information first found in Schwartz’s “Tevuot Haaretz,” adding that when Obadiah of Berinoro (circa 1485) stopped over there there were only Rabbanites residing there. Therefore, coming to the conclusion that the Karaite settlement there was short-lived.

Avraham Yaari is his seminal “Mase’ot Erets Yisra’el” (Tel-Aviv, 1946) reprints three early modern Karaite travel accounts from an earlier publication by Gurland. These are as follows:

No. 14 Samuel b. David from the Crimea (1641-42), pp. 221ff.

No. 16. Moses b. Elijah Halevi from the Crimea (1654-55), pp. 305ff.

No. 21. Benjamin b. Elijah from the Crimea (1785-86), pp. 459ff.

All three travelers visited Hebron. See pp. 247ff. (Samuel), pp. 316ff. (Moses), and 473-74 (Benjamin). From all three accounts, it is clear that there were no Karaites in Hebron: our travelers dealt exclusively with the tiny Rabbanite community upon whom they relied for hospitality. It seems that they were well treated and gave gifts/donations. But in Benjamin’s account, we finally get a tantalizing bit of evidence that may connect to Schwartz’s statement; see p. 474, 11 lines from the bottom:

וחנינו בבתי הרבנים, והם בתי הקראים מקודם.

[I am indebted to Prof. Daniel Frank, from Ohio State University, for bringing Ya’ari to my attention.]

An additional source, which may be of interest, comes from Rabbi Hayyim Yosef David Azulai, known as the Chida. He writes:

“הרב מלכיאל שבא לחברון והיו מתים הקראים ונכנסים ישראל במקומם”. (זכרון מעשיות ונסים של החיד”א ע’ פג, בתוך ספר החיד”א – קובץ מאמרים ומחקרים. ירושלים תשי”ט).

Does this mean that the Karaite community was composed of elderly residents and as they died out, newly arrived Rabbanites came to take their place? Certainly a possibility, as Jerusalem became a haven for elderly Jews who came on aliyah in order to spend their waning years in the holy city. Perhaps Hebron served the same purpose for Karaite Jews during that period?

I scoured through the two-volume “History of the Karaites” תולדות היהדות הקראית by Yusef Elgamil (a Karaite historian) but only saw scant mention of a Karaite connection to Hebron.

The book also reproduces a photo of some Karaite Jews (it is unclear who the people in the photos are exactly) visiting the Karaite cemetery in Hebron after its taking by Israeli troops in the ’67 war.

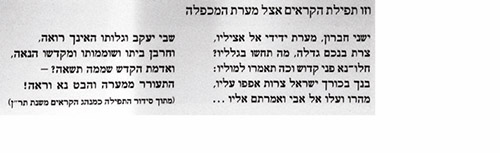

To be sure, Karaite Jews, like all other Jews, revered Hebron as a holy city. They regularly came on pilgrimage and recited special prayers at the Cave of Machpelah (in itself interesting as Karaites traditionally shunned gravesite vigils). This for instance is a medieval Karaite prayer to be recited at the cave (from the Karaite siddur):

A hypothesis may be proposed wherein the Karaite graveyard does not indicate that there was a long-standing Karaite community in Hebron but rather that Karaites—like their Rabbanite brethren—interred their dead there because of a longstanding belief among medieval Jews about the spiritual benefits of being buried next to the Cave of Machpelah.

The Custom Not to Write Names on Tombstones

There was an ancient custom among the Jews of Hebron not to inscribe names or dates on tombstones. As a result we have a collection of slabs of anonymous chiseled stones. The terrible massacre of Jews by the local Arabs in 1929 saw the destruction of large parts of the cemetery; a road was built right in the middle of it and parts of it were used for agriculture and construction of houses.

When the massacre of 1929 occurred there was a question regarding engraving the names of the dead. A query was sent to Rav Kook, then chief rabbi of Jaffa. He replied in no uncertain terms that this case was an exception and that the graves should be marked “so that it also stands as an eternal remembrance of the horrific crime that occurred.” This courageous halachic decision enabled the Jews to recover some of the remains of the murdered (whose tombstones were shattered and their remains scattered in the period 1948-1967) when Israel re-entered the area after the Six Day War in ’67.

Noam Arnon (a leader of the modern Hebron Jewish community) writes:

למרות המנהג שהיה מקובל בחברון לא לכתוב שמות על המצבות, הורה הרב הראשי הראשון לא”י, הראי”ה קוק זצ”ל, לכתוב שמות על מצבות חללי תרפ”ט כדי לזכור את האירוע המחריד. הוא כתב: “הצרה שבאה עלינו ע”י הרוצחים הטמאים ימ”ש, שהוא דבר נורא ואיום שלא נשמע כמוהו בארצנו הקדושה מימי החורבן, לא שייך לגביו תוכן של מנהג, וחובתנו היא לחקוק לזכרון עולם את המאורע הנורא עם שמות הקדושים הי”ד…והשי”ת ינקום לנו מצרינו, וחרפת צוררינו אל חיקם ישיב, וירים רן עמו ונחלתו בב”א..”. הוראה זו אפשרה לשחזר חלקה זו אחרי שחרור חברון.

This is also mentioned in the book דרכי חסד מאת הרב יצחק אושפאל. He claims that this is based on the famous passage (also quoted by Rambam in Hilchot Avel) from the Jerusalem Talmud, Tractate Shekalim: אמר רשב”ג אין בונין נפשות לצדיקים דבריהם הם זכרונם, which I discussed in my post about praying at graves.

This is a bit of a strange claim since we find plenty of inscribed tombstones from that era that commemorate great people (including the mentioned Rabban Shimon Ben Gamliel himself [possibly the same person; there were several members of this family referred to by that name] at the Beth Shearim necropolis, the High Priest Joseph Caipha et al).

Back to the anonymous tombstones. From whence did this strange custom originate? It is certainly neither a Rabbanite nor Karaite custom, for we don’t see anything of the kind in any of the other graveyards belonging to either.

Joel S. Davidi Weisberger is the founder of the Jewish History Channel and an independent researcher. He would love to hear from you at [email protected].