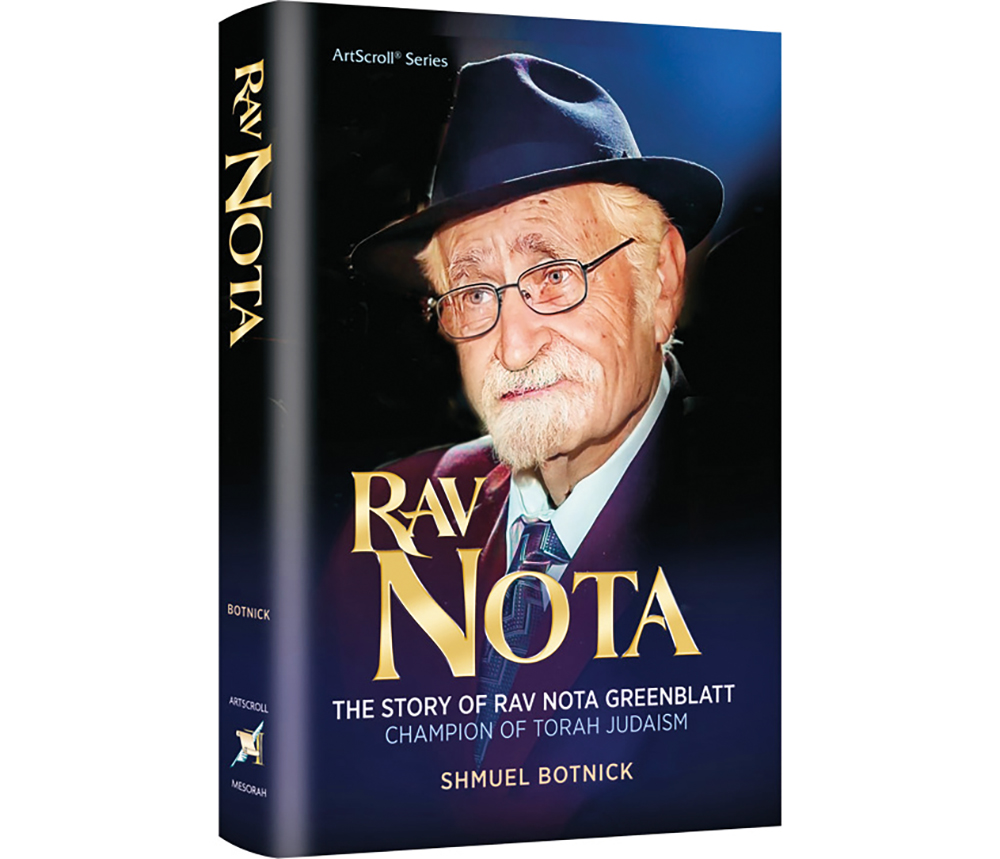

Highlighting: “Rav Nota: The Story of Rav Nota Greenblatt, Champion of Torah Judaism” by Shmuel Botnick. Mesorah Publications Ltd. 2023. English. Hardcover. 320 pages. ISBN-13: 978-1422639726.

(Courtesy of Artscroll) From a quiet community in Memphis, Tennessee came a man whose Torah brilliance, profound compassion and willingness to go anywhere, anytime, to help another made him the rav and posek for thousands of Jews throughout America. Within Memphis, he founded one of America’s first Hebrew day schools, saving an entire community from leaving Orthodox Judaism. Nationally, he helped develop the kashrus standards that we all enjoy today. He brought countless Jews back to Torah observance before the kiruv, outreach, movement ever started. And he traveled hundreds of thousands of miles to write kosher gittin, divorce documents, enabling men and women to rebuild their lives.

His name was Rav Nota Greenblatt, and his story, and the many stories others tell about him, will amaze you.

Rav Nota was a brilliant talmid chacham, one of Rav Moshe Feinstein’s foremost talmidim. Yet he chose to live in Memphis, Tennessee, far from the Jewish metropolises that would have afforded him honor and recognition. But as humble as he was, as small as he made himself, his enormous heart was too big to hide.

The new book, “Rav Nota: The Story of Rav Nota Greenblatt, Champion of Torah Judaism,” magnificently written by Shmuel Botnick, is the story of humility and Torah greatness, and the endless compassion of a very unique rav.

The following are some excerpts from the new book.

• • • •

Rav Nota Greenblatt was once sitting in the beis medrash of Far Rockaway’s Sh’or Yoshuv and a group of students gathered around him, drawn by his magnetic personality. He began sharing story after story with his riveted audience, describing in impeccable detail his many interactions with the leading gedolim of bygone eras.

“Rabbi Greenblatt,” one boy commented, “you knew such great people. Today, we don’t have anyone like that.”

Rav Nota nodded, deep in thought. He then grew very emotional. “Uber s’veht nuch zein,” he proclaimed. “There will yet be!”

This attitude was evident each time he shared a story about one of his sacred rebbeim. Rav Nota was a masterful storyteller, and his voice quivered at the mere mention of their names. He laughed at the funny stories and shook his head in consternation at the ones he never comprehended.

He loved to tell stories, sharing a revivified past with a hopeful future.

Rav Nota had witnessed greatness throughout his lifetime and was determined to relay it to the next generations.

“S’veht nuch zein!” Rav Nota insisted. “There will yet be!”

• • • •

Rabbi Dr. Shmuel Mandelman’s relationship with Rav Nota had a unique genesis. Long enamored by the great gaon tucked away in southwest Tennessee, Dr. Mandelman made it his mission to receive semicha from Rav Nota. This was an ambitious goal; Rav Nota seldom conferred semicha. Nonetheless, Dr. Mandelman traveled to Memphis and made an appointment to speak with Rav Nota. He arrived at the given time and waited in the study. Rav Nota entered and shared a recently developed Torah thought. Dr. Mandelman responded in kind and the two engaged in conversation, sharing Torah thought after Torah thought for a whopping eight hours. None of this followed the protocol of a typical semicha exam, but that didn’t seem to be a problem. Rav Nota pulled out pen and paper and drafted the coveted certificate.

“Now, what is your mother’s phone number?” Rav Nota asked.

Dr. Mandelman’s eyebrows furrowed.

“Uh, why does the rav need her number?”

“Well,” said Rav Nota, eyes twinkling, “I’m sure you caused her enough headaches.

It’s time to give her some nachas.”

Dr. Mandelman had admired Rav Nota’s prowess as a posek, but, in a later encounter, he also came to recognize his ocean-deep compassion.

It happened when Dr. Mandelman placed a call to Rav Nota on Erev Yom Kippur.

His wife was expecting and there were complications. The question for Rav Nota centered on if and how his wife could break her fast should the need arise. Rav Nota, before addressing the question, issued an unasked-for ruling: “You have no permission to go to shul,” he said with no uncertainty. “You will daven at home.” They then discussed the question, reached a halachic conclusion, wished each other a gmar chasimah tovah, and ended the conversation.

Yom Kippur came and went, and all was well in the Mandelman home. After nightfall, they made Havdala and, sometime later, Dr. Mandelman’s phone rang. He glanced at the screen: Why was Rav Nota calling? It turned out to be a brief conversation.

“Reb Shmuel,” said Rav Nota, “how did Yom Kippur go? How is your wife doing?”

Dr. Mandelman assured him that all was well and hung up the phone. It took some time before he realized that Memphis was an hour behind Eastern Standard Time. Rav Nota had called just

moments after his own Havdala.

This was an ongoing facet in Rav Nota’s model of issuing halachic rulings; he provided the relevant answer, but was always sensitive to the circumstances that lay behind the question.

• • • •

Rav Nota Greenblatt carried his experiences in Yerushalayim throughout his lifetime, in one instance quite literally. For decades to come, Rav Nota would tell of his encounter with his brothers’ rebbe, Rav Avraham Yitzchak Kook zt”l. Rav Nota described how he had been a weak child and, at the age of 9, his health began to seriously decline. His concerned father brought him to Rav Kook to receive his bracha for a full recovery. Rav Kook pulled young Nota under his tallis and gave him a heartfelt bracha, reciting the pesukim of Birkas Kohanim. He then davened for Nota’s refuah sheleima and concluded with the blessing that he “live a long life and become a talmid chacham.” Rav Nota was mesmerized by this story. He relived those minutes that he stood beneath the tallis, watching a tzaddik daven on his behalf.

The effects of Rav Kook’s bracha were evident for nearly 90 years, as Rav Nota traveled from city to city, often surviving on only matzah and sardines, going to sleep after 11 p.m. and, not infrequently, rising in the predawn hours to catch his next flight.

When he was 92 years old, he was staying in the home of Rabbi Yosef Grossman in Houston, Texas, when Rabbi Grossman noticed that he looked somewhat uncomfortable.

“Is everything okay?” Rabbi Grossman asked.

“I have a headache,” Rav Nota admitted.

“Can I get you an Advil?” Rabbi Grossman offered.

“Advil?” Rav Nota responded. “In all my life I took only six pills! I have a bracha from Rav Kook—who needs pills?”

Indeed, until his final illness, Rav Nota very rarely visited a doctor.

But Rav Kook had given two brachos: one, that he live a long life; the other, that he become a talmid chacham. Rav Nota would quip that “at least the first half came true.” Undoubtedly, Rav

Kook himself would have differed with him on this.