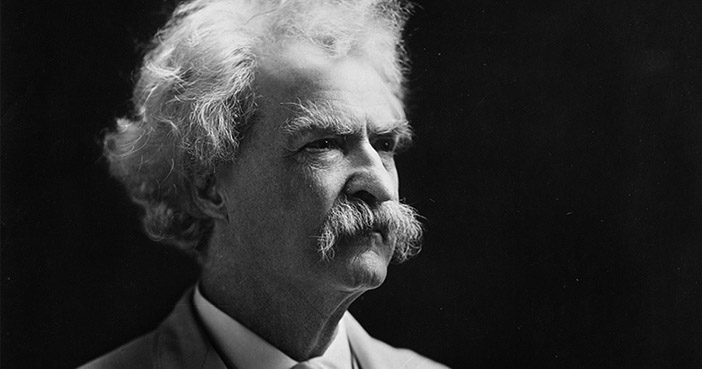

In 1867, Mark Twain visited Palestine in a well-documented journey. As he crisscrossed the barren landscape he offered the following description and observation:

“We traversed some miles of desolate country whose soil is rich enough but is given wholly to weeds—a silent mournful expanse… A degree of desolation is here that not even imagination can grace with pomp of life and action. We reached Tabor safely…We never saw a human being on the whole route…We pressed on toward the goal of our crusade, renowned Jerusalem. The further we went the hotter the sun got and the more rocky and bare…the landscape became… There was hardly a tree or a shrub anywhere. Even the olive and the cactus, those fast friends of a worthless soil, had almost deserted the country. Palestine sits in sackcloth and ashes. Over it broods the spell of a curse that has withered its fields and fettered its energies…”

This sterile and infertile landscape Twain beheld in the 19th century was accurately foreshadowed in Parshat Bechukotai. The parsha contains horrific accounts of destruction and exile. If we betray our Divine warrant to live in Israel, we will be exiled, and our cities and structures will be demolished. Following the description of this wreckage the Torah announces: I will destroy the land and your enemies will be desolate (shemama) while residing in Israel. It would appear that this additional verse describes a condition of the Land of Israel during the galut—beyond the painful removal of the Jewish people.

Famously, the Ramban claimed that this announcement is actually welcome news. During our extended centuries-long absence from the land, no nation or culture will succeed in tilling the land for its fertility or establishing lasting empires in Israel. For centuries, successive empires—whose influence spanned the ancient world—endeavored in vain to conquer Israel and establish their lasting presence. However, Israel didn’t yield its fertility nor did it allow entrenchment. Firstly, the land still carried the Divine curse, which could only be alleviated by our return and our rehabilitation of the land—whose integrity and honor we tragically compromised through our errant behavior. Moreover, the land itself could not yield its fertility to strangers; she waited patiently for her children to return and harness her full potential. Until we returned, the land remained inactive and defiant.

The Ramban didn’t just abstractly write about this phenomenon—he lived it in a very personal fashion. In 1267 he emigrated from Spain to Israel and witnessed a fledgling Jewish community attempting to establish itself. The time for the full return of her children had not yet arrived and Jews weren’t successful in instituting large communities. The city of Jerusalem could barely muster a minyan of 10 men!!

However, dramatically, none of the prevailing empires could deeply embed themselves in a land that continued to refuse long-term admittance to foreigners. In the roughly 120 years between 1177 and 1291 numerous wars were waged over cities in Israel and particularly over Yerushalayim. Saladin fell to the Crusaders in 1177, only to defeat them 10 years later. Just four years later, in 1191, he fell to the armies of the third Crusade. In the latter half of the next century, Crusader armies would fall to invading Egyptian forces. The land was in outright convulsion and all human attempts to occupy and develop this land were futile. The prophecy of Bechukotai—which the Ramban decoded—was in full display to the Ramban and his contemporaries.

Less than 15 years after Twain’s visit through the wastelandsof Palestine, history shifted and the land reawakened. Our motherland opened her arms to her lonely children returning. Deserts and arid lands once again bloomed with lush verdant landscapes and produced fruits and crops that had been largely absent for two millennia. Malaria-infested swamplands were drained to forge modern cities such as Petach Tikva and Chadera. Through great devotion, and sometimes at the cost of life, large terrains that had lain dormant are now teeming with Jewish life. Facing the challenges of limited water supply in an urbanized modern world, we have learned to conserve our sweet water while sweetening our hard water along the coasts. While we continue to daven for Heavenly rain we try to provide as much water for our land and her residents.

Beyond the agricultural renaissance, we have managed to construct a modern democracy upon a land that witnessed the brutal force of totalitarian rule since Titus demolished the Beit Hamikdash. Democratic freedom coupled with economic welfare are not common in too many modern countries and even less so in our part of the world. Part of the resuscitation of Israel is not just the agricultural revival but the construction of a stable and sturdy modern state built upon the principles of freedom and human rights.

We still yearn for the ultimate spiritual revival, the construction of a Mikdash and a state saturated with the presence of Hashem. Until that final stage is attained, history remains incomplete and all our accomplishments remain preliminary. Yet, who can ignore the revival of our homeland, the restoration of its ancestral energy and the joy of children returning home?

Twain was correct: Palestine sits in sackcloth! Israel, however, dances at the constant music of weddings echoing through the cities of Judah and the streets of Yerushalayim. Just as we were promised, the land remained abandoned while we were absent. Our mother waited for us just as we waited for her. The reunion is sweet!

By Moshe Taragin

Rabbi Moshe Taragin is a rebbe at Yeshivat Har Etzion located in Gush Etzion, where he resides.