The Mishna in Sanhedrin 3:3 lists people invalid to testify due to their occupation. These include: one who plays with dice for money, one who lends money with interest, those who fly pigeons and סוֹחֲרֵי שְׁבִיעִית, merchants who trade in shemita produce. Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, a fifth-generation Tanna, notes a linguistic change based on a shift in historical circumstances. Initially, people would call them אוֹסְפֵי שְׁבִיעִית, gatherers of shemita produce. Once the אַנָּסִין (tax collectors) grew abundant, they would call them סוֹחֲרֵי שְׁבִיעִית, merchants of shemita produce.

There’s a Tannaitic background to this cryptic statement of Rabbi Shimon found in Tosefta Sanhedrin 5:2. After initially listing סוֹחֲרֵי שְׁבִיעִית as invalid witnesses, the Tosefta relates: Rabbi Meir would call them אוֹסְפֵי שְׁבִיעִית, while Rabbi Yehuda would call them סוֹחֲרֵי שְׁבִיעִית. To this, Rabbi Shimon said, “I will establish both their words. How so? Before the אונסין grew abundant, they would call them אוֹסְפֵי שְׁבִיעִית; once the אונסין grew abundant, they called them סוֹחֲרֵי שְׁבִיעִית.”

It feels like there was an earlier invalidation of some group associated with improper shemita use. Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Yehuda, both students of Rabbi Akiva,1 had differing traditions as to which group was listed. Rabbi Shimon harmonizes this as either a mere linguistic difference, or perhaps a historical development in the Halacha. Then, our Mishna employs the Rabbi Yehuda language anonymously, pairing it with Rabbi Shimon’s harmonization.

Pumbeditan Dispute

The sugya in Sanhedrin 26a analyzes this cryptic Mishna. Rav Yehuda (bar Yechezkel), a second-generation Amora who founded the Pumbedita Academy, explained that initially they said that אוֹסְפֵי שְׁבִיעִית, gatherers were valid, while merchants were invalid. (This is counterintuitive because Rabbi Shimon saying gatherers were the initial group seems like they were the initial invalid group.) The gatherers were gathering even large amounts for themselves, which was allowed. Then, מִשֶּׁרַבּוּ מַמְצִיאֵי מָעוֹת לַעֲנִיִּים, when people would offer large amounts of money to the poor to gather for them, it was transformed into a business. This led the Sages to declare that both groups were invalid witnesses.

The sons of Rachava, fourth-generation Pumbeditan Amoraim, objected to this because the Mishna says once the אַנָּסִים grew abundant, and they would have preferred the phrase “once the tagarim grew abundant”. Rather, initially both merchants and gatherers were deemed invalid. Once the אַנָּסִין / tax collectors, collecting a property tax, increased. This is as Rabbi Yannai declared, “Go out and harvest during shemita because of the property tax you must pay.” The Sages then said that mere gatherers are fit to bear witness, but not merchants.

Who Is Who?

It’s always good to know the identities of the Sages involved in a sugya, even where it doesn’t majorly impact how we understand the sugya, such as in our case. For instance, who is Rabbi Yannai? There are three candidates. The most likely candidate is Rabbi Yannai II, a first-generation Amora of the Land of Israel and Rabbi Yochanan’s teacher. Certainly Rachava’s sons would know of him. However, if Rabbi Shimon, a fifth-generation Tanna, refers to his decree, a later Amora doesn’t make sense. Similarly, Rabbi Yannai III is a third-generation Amora of the Land of Israel, which similarly doesn’t make sense.

The final candidate is Rabbi Yannai I, a fifth-generation Tanna who appears in Avot 4:15 andsaid: “It is not in our hands either the security of the wicked or the afflictions of the righteous.” We encountered this same Rabbi Yannai in Tosefta Sanhedrin 2:2 and Sanhedrin 11a quoting Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel’s reasoning for intercalating a year. Even with this identification, is fifth-generation Rabbi Shimon stating that this shift in shemita practice occurred in his own generation?

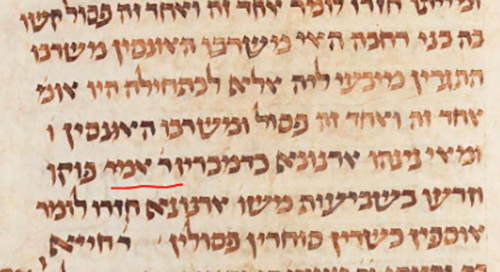

In fact, any of these Rabbi Yannais makes sense, because the Talmudic text is כִּדְמַכְרִיז רַבִּי יַנַּאי, “as Rabbi Yannai announced.” Rachava’s sons are suggesting that there was a decree due to property tax, just as in a different generation, Rabbi Yannai made this announcement due to property tax. Indeed, that is why the girsa in Florence 8-9 identifies the speaker as s Rabbi Ami, a third-generation Amora of the Land of Israel, announce this decree.

Additionally, who is Rachava and who are his sons? Rachava I, a contraction of Rav Achava, was a third-generation Pumbeditan student of Rav Yehuda (bar Yechezkel). He married Choma, great-granddaughter of his teacher Rav Yehuda. (Rav Yehuda’s son Rav Yitzchak had a son Issi who had a daughter, Choma.) After Rachava’s death, Choma married Rav Yitzchak, son of Rabba bar bar Chana; after his death, she married the fourth-generation Pumbeditan Amora, Abaye.

Rachava’s sons were Eifa and Avimi. Sanhedrin 17a, which adds descriptive appellations to actual Amoraim, states that “the sharp ones of Pumbedita” were Eifa and Avima, sons of Rachava, while “the Amoraim of Pumbedita” were Rabba and Rav Yosef. Thus, these sharp Amoraim are arguing with their own ancestor, Rav Yehuda. For another example of their characteristic interaction, compare with Shabbat 103a, where Rabba and Rav Yosef, Pumbeditan Amoraim, interpret a statement in the Mishna in the same way. Again, קָשׁוּ בָּהּ בְּנֵי רַחֲבָה, they object for a stated reason. Therefore, (their stepfather) Abaye and Rava, also of Pumbedita, interpret the Mishna in a different way. Again, none of this leads to a revolutionary interpretation of our sugya, but this biographical background still makes the sugya come alive.

1 See Sanhedrin 86a: אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן סְתָם מַתְנִיתִין רַבִּי מֵאִיר סְתַם תּוֹסֶפְתָּא רַבִּי נְחֶמְיָה סְתַם סִפְרָא רַבִּי יְהוּדָה סְתַם סִפְרֵי רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן וְכוּלְּהוּ אַלִּיבָּא דְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא. Each of these famous students of Rabbi Akiva perhaps presided over the creation of a Tannaitic work, finished by their students, so the unattributed statement aligns with their view.