Mourning is a deeply personal and emotional experience. Merely “going through the motions” without authentic inner sadness yields a listless and empty experience. Mourning ancient tragedies of Jewish history on Tisha B’Av can be challenging in that way. It has historically been a daunting challenge since we lament events that transpired in the distant past. Tisha B’Av in the modern State of Israel is even more complicated. For centuries, Jews were scattered across the globe and mired in hopeless conditions of despair. Living through seemingly endless cycles of persecution and discrimination, it was easier to trace their bleak world to the day we left Yerushalayim. Tisha B’Av may not have been “current” but its footprints were traceable in their everyday lives. Regrettably, we had abandoned our God and betrayed our love and for that we were cursed. Our suffering was the price we paid for our crimes all the while hoping to one day rebuild our great love with God.

That day has come, and our love has been restored. Millions of Jews live in Israel and millions of others live in the spiritual shadow of Israel. Though we still struggle with the final phases of history, our condition doesn’t even closely resemble that of previous generations. Living with triumph and pride, how do we mourn within this unfamiliar historical context? Without updating our mourning, Tisha B’Av can become emotionally disconnected. Even if our imaginations summon genuine tears, the entire experience can become divorced from our day-to-day experience. How can Tisha B’Av be updated to the 21st century to render it not just authentic but relevant? Perhaps by looking back to the past century and to the two seismic events that reshaped the Jewish landscape: the Holocaust and the formation of the State of Israel. If we don’t orient Tisha B’Av around these two history-changing events, we risk severing our mourning from our reality.

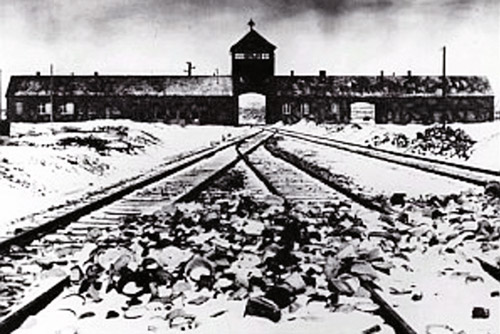

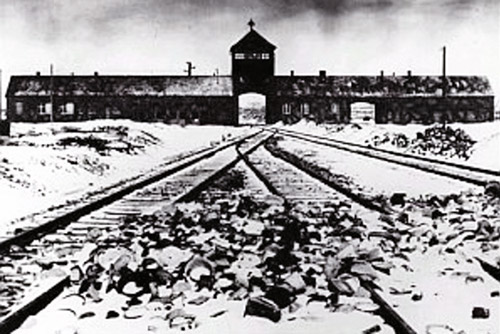

The Holocaust should be seen not just as a horrific tragedy. It was the abyss of centuries of Jewish persecution. Without minimizing the suffering we endured during the long night of Jewish exile, the Holocaust was the single greatest trauma of Jewish history in 2,500 years. No Inquisition, no pogrom, nor no Crusader invasion can begin to compare to the Holocaust in scope and intensity. The Holocaust wasn’t just the darkest moment of Jewish history. It also pulled back the curtain, exposing the horror of antisemitism. Throughout history, violence toward Jews could always be attributed to the general decayed state of humanity: Amidst a general environment of religious intolerance, racial discrimination, and overall violence, hostilities toward Jews felt “natural.” Life in cruel and repressive societies is always fragile, and Jewish life was even more vulnerable in these morally detestable societies.

Remarkably, Europe of the 19th and 20th century had turned the corner and was a continent on the move. Rapid industrialization, economic revolution, political enfranchisement and cultural evolution had all created an environment of confidence, progress and belief in the virtue of man. Humanity had convincingly pulled itself out of the quagmire of corruption and savagery and was hurtling toward a utopian world of science, tolerance and enlightenment. Germany was at the center of this development, spearheading advances in every sector of human progress. Yet, even this progressive and cultured society degenerated into hatred and genocide.

Jews should certainly not define themselves by antisemitism, but we also should not ignore its pervasiveness. This hatred is baked into human history. It can be tamed and curtailed but can never be fully eliminated. Tisha B’Av launched a bleak world of hatred and repression. After extinguishing the light in Yerushalayim, humanity suffered through close to 1,500 years of stagnation and oppression. Over the past 500 years, humanity experienced a renaissance and fashioned a more civil world of ration and morality. Sadly, even the modern, enlightened world isn’t immune to antisemitism. The Holocaust reminds us of the catastrophic impact of Tisha B’Av—the unleashing of antisemitism. This incurable disease has stained the moral consciousness of human history.

The second seismic shift in the Jewish world during the past century was the formation of the State of Israel. How should Tisha B’Av be streamed through this miracle of history? Firstly, by realizing how close we are to the conclusion of history. Ironically, as our appetites have been whetted, Tisha B’Av feels even more devastating. Our ancestors lived hundreds of years apart from redemption. They dreamed and hoped, but it remained elusive and distant. They imagined caressing the stones of the Kotel and kissing the dust of a blessed land. Yet they lived trapped lives, dispersed across continents and strewn across time. We are living at the doorstep of history. As we pray that “our eyes should witness the return to Zion” we are troubled by the prospect that those eyes will go dark before redemption concludes. Will we miss these epic scenes by a mere 10 years? Will redemption happen soon after we have departed this world? These haunting possibilities didn’t occupy our ancestors, but they should worry us and agitate our Tisha B’Av.

In a similar vein, we are so close to the conclusion of this marathon, but yet there is so much more that we hope for. Modern religious Jews who love Israel should always calibrate their redemptive imagination somewhere between triumph and longing. We know how to celebrate the miracles we have experienced but we must also “long” for the fully redeemed state, which is still elusive. If, year-round, we spend too much time celebrating, Tisha B’Av is a day to adjust the balance and remind ourselves to “long” and to yearn for comprehensive geula.

Our return to Israel in the 20th century also unleashed a torrent of opposition to Jewish presence in Israel. We face physical violence, international condemnation and accusations of moral hypocrisy. Some of this opposition is just a manifestation of classic antisemitism dressed in the costume of contemporary politics. However, opposition to Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel is a separate form of animosity. Tisha B’Av is responsible for this struggle as well. We inhabited this land thousands of years ago and were at the verge of creating the kingdom of God. We forfeited that chance on Tisha B’Av and it has been a long odyssey home. The long road home has been fraught with anger and opposition. One day the world will embrace our presence in this land and celebrate Jews in Yerushalayim. The world is still broken and resists us. We broke our world on Tisha B’Av and for this we cry 20th-century tears.

The writer is a rabbi at Yeshivat Har Etzion/Gush, a hesder yeshiva. He has semicha and a BA in computer science from Yeshiva University as well as a master’s degree in English literature from the City University of New York.