By Rachel S. Kovacs

Tamir Goodman renders the word “impossible” meaningless. Impossible to be committed to his faith and his sport, Shabbat and his professional career? Impossible not to burn any bridges after devastating college experiences? Impossible to play after debilitating injuries requiring surgeries? Impossible to live without bitterness, or to make empathy, passion and diversity core values? Not impossible at all.

What accounts for Tamir’s ability to rebound, change directions, and find a niche within his sport that engenders respect for Jews and non-Jews alike? Undoubtedly, positive family influences, and unconditional love and support, have been significant variables. The Baltimore Goodmans attended a Chabad synagogue, where Karl, his father, and his family were active members. As an observant Jewish household, they maintained strong, but not exclusive, ties to Chabad.

Rachamim and Adi, Tamir’s siblings, are Chabad emissaries in England and Florida, respectively. Tamir and his mother, Chava, reside in Israel; the remaining siblings still live in northwest Baltimore. Our families knew each other from the synagogue and schools, yet until I interviewed him, I understood little about what shapes the Tamir Goodman of today, or how, decades before Beatie Deutsch and Ryan Turell, he blazed a path for Orthodox athletes.

Tamir’s father, Karl, a successful attorney who passed away in 2011, was, Tamir said, “unique”— a proud Jew who wore his yarmulke in court when it was not yet common practice to do so, and a man whose home was open to all. His father once invited the entire Morgan State University women’s basketball team for Friday night dinner. Karl, dubbed “Ish Tov,” a good man (the literal translation), was highly respected by non-Jewish clients for his kindness and ability to identify the essence of a problem and solve it.

Karl’s Jewish pride manifested itself in family participation in Crown Heights’ Lag B’Omer parade and in encouraging Tamir’s connection to the Lubavitcher Rebbe and basketball as a shomer Shabbat. In 1980s Baltimore, all teams played on Shabbat, yet Tamir’s family never suggested that the sports world would not accommodate his religious needs or that his dream was impossible. Karl believed that by infusing the physical, e.g., basketball, with the spiritual, one could accomplish many things. When Tamir experienced antisemitism on the court, Karl would tell him, “Let your game do the talking.” Karl’s influence pervaded Tamir’s education and his pro-basketball and entrepreneurial careers. Chava, his mother, always had his back.

Chava Goodman is Israeli. Her late mother, or Savta, who survived Bergen Belsen, lived with them half the year. Savta told Tamir that there wasn’t a day when she didn’t think about the war. Her choice to be happy, and make others happy, despite the war and the loss of her only son, was empowering to Tamir, as was her support for him. He choked up as he conveyed her closeness with his family, a privilege that children and elderly Shoah survivors rarely share.

Tamir left Baltimore for high school at Chabad yeshiva in Pittsburgh. Despite his friends and love of learning there, he soon realized that his life’s mission was professional sports. Chava approved, with the caveat that Tamir complete ninth grade in Pittsburgh before transferring to Baltimore’s Talmudical Academy. “TA,” his previous school, had an active basketball program. Tamir left Pittsburgh on good terms with his teachers, teammates and mentors.

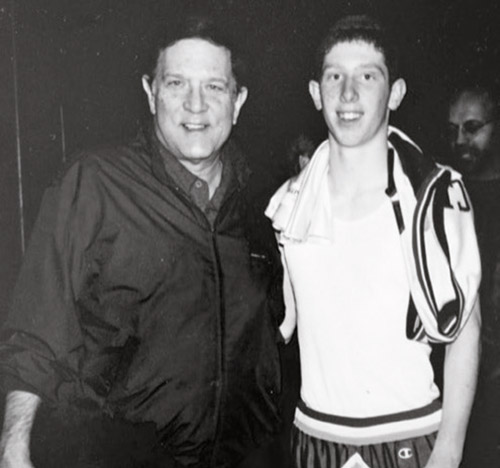

TA for 10th and 11th grade was “so magical to me,” Tamir noted, because of the diversity he encountered, proximity to his family, and the joined-at-the-hip connection to his coach. Harold (Chaim) Katz inspired the TA team and to this day, is Tamir’s lifetime mentor and friend. He still calls Coach Katz from Israel, often several times each day, to get his advice. His feelings for him? “You were so many years ahead of the time in so many ways. Basketball. Education. Religion, etc., etc.”

Coach Katz told the team that they did not need to be there, but “if you’re going to be here, be on time, do well in school, don’t embarrass your Creator…” They would have to work “very, very hard… but… I promise you, it will be the greatest ride of your life.”

For Tamir, it was the greatest ride, for a while. He ranked 25th in the nation in basketball. A University of Maryland scout dangled a basketball scholarship, and then, in early 1999, as a junior of 17, Tamir was offered a place on their Division I team, and “Jewish Jordan” was profiled in a Sports Illustrated article (https://tinyurl.com/4pfvk3dw). But Coach Katz viewed the comparison as unfair to both Tamir and Jordan. (https://tinyurl.com/2p9d72p9).

Tamir achieved national recognition. He was a hit in America’s heartland. When I taught in Peoria, a colleague asked about “Jewish Jordan.” I was clueless. He produced the article, and I said “Sure, I know him,” with a smile.

Back in Baltimore, overflow crowds filled the TA games. The administration viewed the growing fan base and attendant media blitz as antithetical to the school’s goals. Female fans were at best a distraction to its students, and gym capacity concerns were real. As Tamir put it, administrators were moving the school in a different direction. They decided that the team would subsequently play “away” games and suggested that Tamir would be best off elsewhere. In time, TA eliminated the basketball program altogether. Yet, in characteristic style, Tamir harbored no ill will, and is in contact with his teammates and Rabbi Teichman, former TA principal.

Given his commitment to basketball and to Shabbat, Tamir’s switch from TA to the Seventh Day Adventist Takoma Academy was an opportunity to do both; significantly, it was a senior’s lesson in mutual respect. He learned Torah with rabbis from the Yeshiva of Greater Washington in the afternoons, and on occasion, brought the Adventist’s team to Max’s kosher restaurant in Silver Spring for lunch. Sometimes, Rabbi Elchonon Lisbon, whose bookstore was a few doors away, would see Tamir near Max’s and learn with him.

In summer 1999, Tamir began practicing at Cole Field House on the Maryland campus. Then the ride of a lifetime took a downward turn, at first slowly, and then precipitously. Maryland’s agreement exempting Tamir from games on Shabbat and holidays was not honored. So Tamir transferred to Towson University, a respected college in the University of Maryland system, which was much closer to his home. Things seemed to improve, until Towson fired its basketball coach and hired a new one. In the locker room, the latter allegedly assaulted Tamir. Although no criminal charges were filed, Tamir was through with Towson and college basketball. He had already sustained injuries that had an impact on his game, but this was the final straw. Tamir questioned whether he could endure another setback, but in hindsight, “My best move was getting up after getting knocked over.”

Almost every life-changing event can be considered either a defeat or an opportunity to change directions, to “pivot.” Tamir saw it as a blessing that enabled him to follow his dream of living and playing basketball in Israel, near his Savta. The blessing multiplied. He met his wife, Judy, who came to Israel from Cleveland; an athlete, trainer, dietician, and writer, she attended university there. Two weeks after meeting, they were engaged, and 19 years and five children later, they are a team. They recently collaborated on a book.

Tamir realized his dream to play for Maccabi teams across Israel, but painful injuries made team sports unsustainable. After knee injury No. 1, his mother said, “Maybe it’s time.” Tamir responded: “No way.” He battled injuries until 2009, at 27, and left professional sports. Had his health and a better game prevailed, he posits, any blessings that accrued after losing his dream, at the height of his career, never would have materialized. He played sports to the end and thus, helped fulfill his mission.

The next step for Tamir was to finish college. At University of Maryland’s University College, he majored in communications. He now uses his cumulative knowledge and experience to assist the next generation of players. His experience with severe dyslexia helps him adapt to diverse students and learning styles. With tutoring, he scored just high enough on the SATs to secure his Division I scholarship. He made the dean’s list in college, “because the SATs did not define your intelligence, or your work ethic, or your character,” as he tells special needs students.

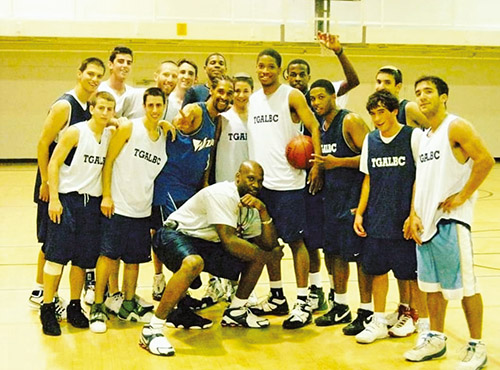

From 2009-2013, Tamir, Judy and family relocated to the U.S., where he ran basketball camps and programs. When they returned to Israel, he resumed training highly diverse students—over 5,000—“the next generation of players.” But during COVID, about 98% of his work, involving the airports, tourism, and basketball (international camps and clinics) vaporized. Yet again, Tamir pivoted. He invented various devices, one for the NBA, one to disinfect basketballs, sports-adapted tzitzit; developed programs for Israel’s sports tech scene, StandwithUsTV (exercises, with 16,000 participants); wrote two books with Judy (one upcoming), and a pending documentary.

The one consistent, overarching goal that has dominated Tamir Goodman’s life is his desire, shaped by his personal experiences with diversity, to use sports as a platform to unite and educate people, so that hate, racism and antisemitism will be obliterated. His college roommate was a Muslim basketball player, with whom he is still “super close”; his early teammates in basketball camps were primarily African American; and his students are even more diverse. He’d love to share the magic of what happens when people from diverse backgrounds come together and form lifelong friendships. “The world is a much more beautiful place that way, and it’s a big part of what I’m doing now.”

Rachel Kovacs is an adjunct associate professor of communications at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at [email protected].