One of the most emotion-charged campaign platforms of the 2016 election cycle was the declaration by candidate Donald Trump that the U.S. should build a wall along its southern border as a way to stop illegal immigration.

Perhaps ironically, the week of President Trump’s inauguration the Daf Yomi cycle began Bava Batra, which opens by saying that if two partners wish to divide a property, they should build a wall on the border.

The aim to build the border wall in the U.S. took on much deeper meaning. For some it showed concern for U.S. safety. To others it seemed to underscore xenophobic feelings. Nobody really viewed it as just a wall, a collection of materials designed to demarcate a boundary that already existed.

In Jewish life, we also have a concept of boundaries and lines we won’t cross. We are supposed to make sure we set up safeguards for the mitzvot, but interestingly, Chazal don’t suggest a wall. In Pirkei Avot, the Anshei Knesset Hagedolah are quoted as saying, “Make a fence around the Torah.” This refers to various rabbinic prohibitions designed to prevent us from transgressing Biblical ones.

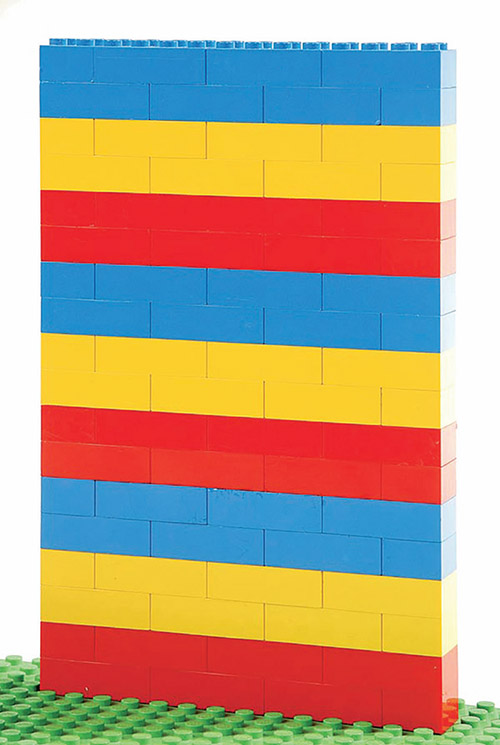

The question is: why do we build a fence? One can easily get over a fence (hence the idea of a border wall) and get to the other side. Why don’t they say we should build a wall? Concrete, 4 feet thick, with electrified barbed wire and laser beams to deter or destroy trespassers?

If we want to really protect the Torah from being transgressed, shouldn’t we establish much more rigorous standards for behavior?

I’d like to suggest that the problem with building a wall is that it becomes the center of attention, and not what it was intended to protect. As long as we have a fence, meaning something similar to the prohibition that reminds us not to do what Hashem warned us against, we will focus on doing Hashem’s will. When the fence becomes a wall, however, our vision is impaired and we stop seeing the actual mitzvah. Just as the conversation in America turned to “wall or no wall,” instead of immigration, our focus becomes the barrier itself but we forget why it was erected to begin with.

Take Pesach cleaning, for example. We don’t want to have chametz in our homes. This could be easily avoided by getting rid of our chametz as best as we can and then making anything left null and void. Once you do that, you’re in the clear. But for many of us, cleaning for Pesach took priority and it turned into spring cleaning.

Pesach started to be associated with the vilified “wall” of cleaning more so than with the purity and humility of not having chametz. How many people get angry when someone walks into a room they’ve already cleaned? In defense of this wall, they will transgress numerous other Biblical sins such as anger and hurtful words, in the process utilizing their egos that were supposed to be diminished as part of the Pesach preparations.

Smartphones are another one. The reason they are so deadly is because of the access to so many horrible things, from inappropriate images to lashon hara on steroids. Of course, those same phones can also be used to spread Torah and kindness and do just as much good, since zeh le’umat zeh asa Elokim, Hashem balances everything—so as bad as it can be, that’s how good it can be.

Many rabbanim have decried the use of these devices, and that’s a valid approach to stopping the dangers. However, when the smartphone becomes the evil itself, and we lose sight of what we’re supposed to be protecting, we’ve built a wall instead of Chazal’s fence. Instead of knowing that Hashem wants us to use our eyes and our speech for holy and good purposes, we only learn that somehow He is against technology and this phone is some sort of an idol. When it becomes proper to speak lashon hara about or steal from someone because he or she has a smartphone (and not because he’s not listening to his rav), we’ve crossed a line we should not have crossed.

When a community had a particularly heated public disagreement about an eruv, one wise rabbi commented, “Carrying in this area is only a rabbinic prohibition, but the lashon hara is a Biblical one.” When people in another place wanted to stop an eruv from being used, they vandalized it just before Shabbos. In order to prove their point, they were willing to cause chilul Shabbos by ensuring that according to no opinions had the sanctity of Shabbos been upheld.

And it’s all because we put up a wall and couldn’t look beyond it. So, as we move forward, perhaps we can poke some holes in the walls. Not big ones that people could slip through, but just large enough that we can see through them to remember that we’re trying to do what Hashem wants from us on all fronts.

By Rabbi Jonathan Gewirtz

Jonathan Gewirtz is an inspirational writer and speaker whose work has appeared in publications around the world. You can find him at www.facebook.com/RabbiGewirtz, and follow him on Instagram @RabbiGewirtz or Twitter @RabbiJGewirtz. He also operates JewishSpeechWriter.com, where you can order a custom-made speech for your next special occasion. Sign up for the Migdal Ohr, his weekly PDF dvar Torah in English. E-mail info@JewishSpeechWriter.com and put “subscribe” in the subject.