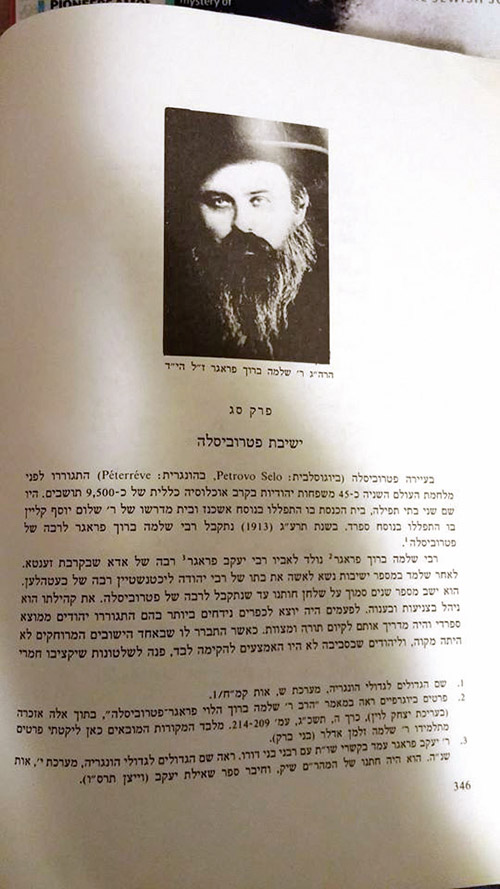

Rabbi Shlomo Baruch Halevi Prager (1887-1943) was the Ashkenazi chasidic rav of Bačko Petrovo Selo in Serbia (his father, Yaakov, was the rabbi of the nearby Serbian village of Ada). He was apparently somewhat unique among the Hungarian charedim in that he engaged in “kiruv” activities. He would travel to remote Yugoslavian villages in order to teach Torah and spread knowledge of Judaism to Ladino-speaking Sephardim. Although the bulk of Serbian Sephardim lived in the capital of Belgrade and Southern Serbia, there were also Ladino-speaking Sephardim in villages of Northern Serbia, close to the Hungarian border.

He sought out Jews who were completely ignorant of the fundamentals of Judaism and taught them Torah. He also erected mikvaot and settled disputes. According to the historian of Hungarian charedim, Abraham Fuchs, in his two-volume “The Yeshivot of Hungary”:

“He would travel to far-flung remote villages in which secular Jews lived. He would erect a ritual bath for them and bring them closer to Torah. An example of his righteousness: As a result of his frequent travels, his community would give him a certain sum of money to cover his travel costs, but Rabbi Prager preferred to save the money and spend it on charity—and instead of taking public transportation he would walk long distances by foot. When his community got wind of this extraordinary activity, they decided to remit his salary to his wife so he wouldn’t spend all of it on charity.”

See Fuchs, “Yeshivot of Hungary” Vol II, p. 346.

The Serbia of pre-World War II (and Yugoslavia in general) was one of the most diverse Jewish diasporas in the world. It contained everything from Romaniotes (Jews who had been in Europe since the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE) to descendants of Sephardic Jews who had emigrated from the Iberian Peninsula, to regular Ashkenazim and various types of chasidim.

In the former Yugoslavia, the existence of Sephardic and Ashkenazic communities side by side is well known. Zemun, Serbia, is where Theodore Herzl’s paternal family came from. It was Theodore’s grandfather, Simon Loeb Herzl, who was close with the Serbian Sephardic rabbi and proto-Zionist Rabbi Judah Alkalai. That region was unique in that Sephardim and Ashkenazim came into contact with each other early on and developed close relations (there is even a theory that Herzl himself was of Sephardic lineage).

By the way, speaking of Rabbi Avraham Fuchs, he was a very interesting and multi-faceted individual in his own right. Hungarian-born and deeply Orthodox, he studied at the Tasnad Yeshiva in Hungary as a youth. While not chasidic, he retained a deep affection for Hungarian rabbis, chasidic and otherwise. He wrote the first official biography of the Satmar Rebbe back in 1981. Fuchs married the daughter of the Syrian Halabi Hakham Mordechai Attiya who was a renowned rabbi and Kabbalist—first in Mexico City and then in Jerusalem. His father-in-law and his brothers-in-law were (and are) all affiliated with the Religious Zionist rather than the charedi community.

There is an effort underway to translate Fuchs’ book on Hungarian yeshivot into English.

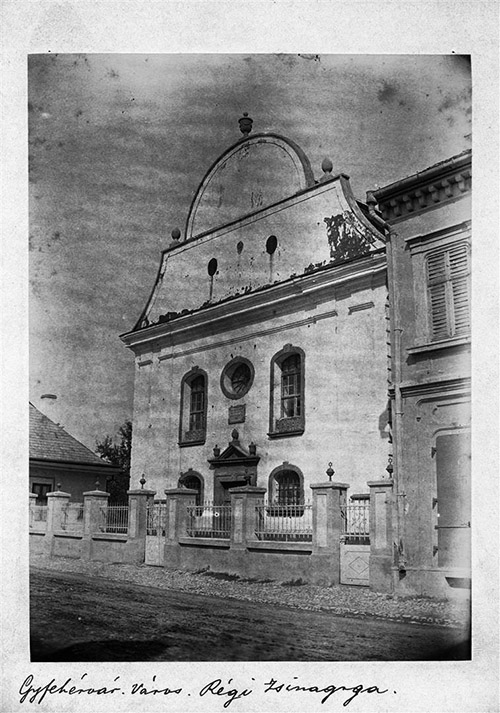

Rabbi Yechezkel Paneth served as the chief rabbi of Karlsburg (Alba Iulia) in Transylvania from 1823 until his passing in 1845. Paneth’s grandson, Yissachar Dov Friedman, wrote a biography of his grandfather titled Toldot Mareh Yechezkel.

In the book, Friedman records several interviews he conducted with several elderly Sephardic members of the community who recalled Rabbi Paneth with great reverence and fondness (Rabbi Paneth, though a staunch charedi Ashkenazi conservative, would make it a point to pray every other Shabbat at the Sephardic synagogue). Friedman recalls how, with tears in their eyes, the elderly Sephardic men reminisced about their departed rabbi, “We are not worthy of mentioning his holy name; there has never been and there never will be one like him. All Jews—Sephardim and Ashkenazim alike—were equal in his eyes. He would pray in our synagogue every other Shabbat and give a sermon. He would also attend services by us on the first two nights of Passover because we recite Hallel after the evening prayers [Rabbi Paneth, though originally a practitioner of the Ashkenazic rite, took on chasidic customs]. He also prayed by us on the eve of Shemini Atzeret because we conducted hakafot then. His face shone like an angel from heaven as he danced with the Torah scrolls. The community raised both him and the Torah and danced with them around the Bima [Tebha] seven times.” See תולדות מראה יחזקאל בהקדמה לשו”ת דרך יבחר.

Joel is an independent researcher of Jewish history—with a particular interest in the fluidity of Jewish subethnic and religious identity in the Medieval and modern periods—and a translator of Hebrew text (he also misses being a scholar-in-residence during non-COVID times). He can be reached at yoelswe@gmail.com.