Part I

What is the connection between a city in Spain, two Jewish martyrs, a moralist rabbi, and a socialist activist?

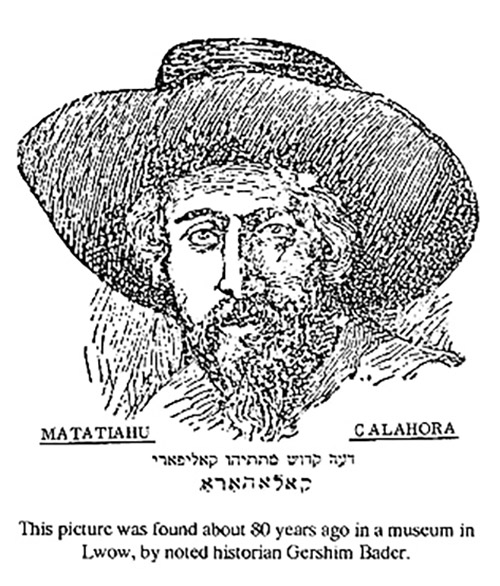

This has been misattributed to Calahora when in fact it is a drawing of the famous Yashar of Candia.

Dr. Solomon Kalahora, personal physician to the Polish monarch Sygmund August (1520-1572) and his successor King Stephen Bathory (1533-1586), was a Sephardic Jew (in some sources a converso) who settled in Cracow, Poland, in the 16th century. Though the Kalahoras (the name would later undergo many variations and changes including: Kolhari, Kolchor, Kolchory, Kalifari, Calaforra, Kalvari, Landsberg Posner, Zweigenbaum, Rabowsky, Olschwitz and Milsky) had come to Poland from Italy, the family name was based on the name of the Spanish town of Calahorra from where the family originated.

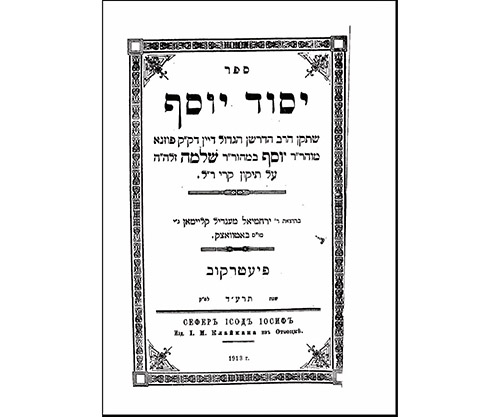

Of the patriarch Solomon’s six children, Moses continued the family branch in Cracow, and Israel Samuel (1560-1640), the rabbi of Lenchista, founded the Poznan branch. One of Israel Samuel’s sons was Matityahu Calahora (pictured), who according to the contemporary Polish historian Kochowski was a “well-known physician with an extensive practice in Christian and even clerical circles.” Matityahu’s life came to a violent end when he became embroiled in a religious dispute with a Dominican friar named Havlin. The Russian- Jewish historian Simon Dubnow describes the event, disturbing in its sheer brutality:

“The priest invited Calahora to a disputation in the cloister, but the Jew declined, promising to expound his views in writing. A few days later the priest found on his chair in the church a statement written in German and containing a violent arraignment of the cult of the Immaculate Virgin. It is not impossible that the statement was composed and placed in the church by an adherent of the “Reformation or the Arian heresy,” both of which were then the object of persecution in Poland. However, the Dominican decided that Calahora was the author, and brought the charge of blasphemy against him. The Court of the Royal Castle cross-examined the defendant under torture, without being able to obtain a confession. Witnesses testified that Calahora was not even able to write German. Being a native of Italy, he used the Italian language in his conversations with the Dominican. In spite of all this evidence, the unfortunate Calahora was sentenced to be burned at the stake. The alarmed Jewish community raised a protest, and the case was accordingly transferred to the highest court in Piotrkow. The accused was sent in chains to Piotrkov, together with the plaintiff and the witnesses. But the arch-Catholic tribunal confirmed the verdict of the lower court, ordering that the sentence be executed in the following barbarous sequence: first the lips of the “blasphemer” to be cut off; next his hand that had held the fateful statement to be burned; then the tongue, which had spoken against the Christian religion, to be excised; finally the body to be burned at the stake, and the ashes of the victim to be loaded into a cannon and discharged into the air. This cannibal ceremonial was faithfully carried out on December 13, 1663, on the marketplace of Piotrkov. For two centuries the Jews of Cracow followed the custom of reciting, on the 14th of Kislev, in the old synagogue of that city, a memorial prayer for the soul of the martyr Calahora.”

Matityahu’s son Michael and his two grandsons were also notable physicians in Poland. Matityahu’s brother, Solomon Calahora, married the daughter of the Posen physician, Judah de Lima (another Sephardic family that settled in Poland, of whom we shall talk more later).

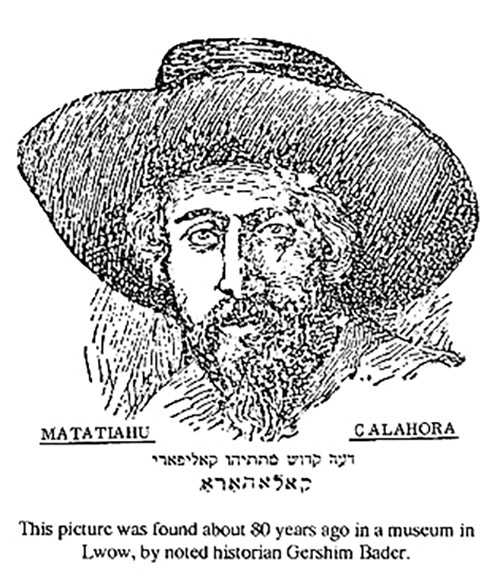

One of Solomon’s sons was Joseph (1601-1696), also known as Joseph Darshan (literally, preacher) of Poznan who authored a popular work on ethical and moral obligations, Yesod Yosef, published in Frankfurt in 1679 (pictured). Joseph’s son, Aryeh Leib Kalifari, a preacher in Posen, was the founder of the Landsberg and Posner families. Aryeh Leib became the second member of this family to be martyred when he was arrested and tortured by the Catholic authorities in 1735 in the course of a blood libel. Heinrich Graetz describes the event in his “History of the Jews”:

“Adalbert Yablonowitz, a son of a prominent citizen, disappeared from his home and his mutilated body was found in a village near Posen. The Christian population of Posen…at once charged the Jews with the crime. The majority of the Jews of Posen, fearing violence, fled for their lives. The preacher, Aryeh Leib; the communal representative Jacob ben Pinhas; and two parnasim, Isaac and Hertz, were seized and thrown in prison. The preacher and the representative were tortured and died in prison (Aryeh Leib rebuffed an offer to spare his life if he converted—J.D.). The trial of the parnasim and five other prominent Jews dragged on for nearly four years when a foreign community, Vienna, it seems, procured an able advocate who succeeded in proving the innocence of the accused and the latter were released in 1740.

Aryeh Leib’s great-grandson, Solomon Posner (1780-1863), was the author of a family chronicle, “Toar Penei Shlomo.”

Stanislaw Posner (pictured), pseudonym Henryk Bezmaski (1868-1930), was a grandson of the aforementioned Solomon Posner and a Polish socialist activist, senator, lawyer and publicist. He also authored “Poland as an Independent Economic Unit.”

The author is the founding editor of Channeling Jewish History and can be reached at yoelswe@gmail.com.