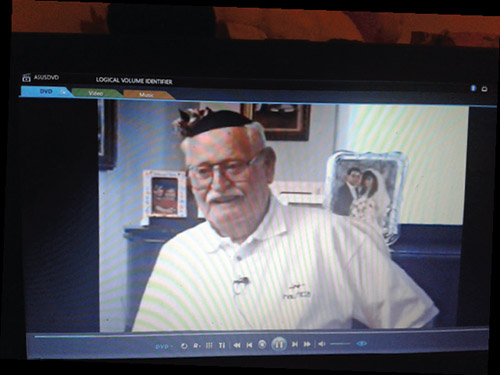

My father, David Roth, was born on March 26, 1913, in a small city called Bereg, near Beregsazs, in the Carpathian Mountains. My father was the third-youngest child of eight, six boys and two girls. He, as did his brothers, went to cheder in Beregsazs, and after his bar mitzvah went to learn in a neighboring town, called Savelyev. During these years Zionism was growing, and my father, even though his family was affiliated with the Spinka chssidic sect, joined the HaShomer HaTzair Zionist movement.

As was the case with all young men at the age of 18, he was conscripted into the Czech Army. I learned that he was a member of the Army’s Ski Patrol. I discovered in my adult life that my father spoke German fluently, and because of that he was part of the Czechoslovakian military team that translated the documents during the ceding of the Sudatenland by Czechoslovakia to the Nazis prior to the outbreak of World War II.

My father survived the Dachau Concentration camp and was liberated after four years by the American troops in April 1944. When he was liberated he was 31 years old. His weight was barely 40 kilo, roughly 85 pounds. Both of my parents were Holocaust survivors. My mother met my father after the war in Prague, where they got married. They came to the U.S. in 1948.

Neither of my parents spoke about their experiences during the war. My only clue to their being survivors was that when my sister or I were misbehaving, my mom would say, “For this I survived Hitler?” We assumed it was something bad. Our first exposure to the Holocaust came in May 1960. I was 10½ years old. The newspapers announced that the Mossad had captured Adolf Eichmann. I remember seeing the headline and my mother crying. I asked her who this Eichmann was. Her first reaction threw me for a loop. I never heard or saw my mother express anger. Her response was that they should hang him by his arms and that every Jew should take a knife and cut a piece from his flesh until he was dead. Was this my mother speaking? She then composed herself and explained that Adolf Eichmann was one of the highest-ranking Nazi officers who had been responsible for the murder of six million Jews during World War II. Unlike the other Nazis who were tried and executed at the end of the war, Eichmann, and his fellow Nazi Josef Mengele, managed to escape Europe and were in the wind. She also told us about the atrocities committed by Mengele.

It was after that conversation that I decided I would learn whatever I could about the Holocaust and the murder of six million of our people by the Nazis. Whenever I asked my father about what had happened to him during the war he would shrug his shoulders and say he didn’t want to talk about it. The only thing we knew about my father from his being in “the concentration camp” was the following story, which was told to us by my mother. One day, during the winter, the Kommandant of the camp decided that during roll call, anyone whose height did not reach the Kommandant’s shoulders would be executed. There was a young, sickly boy about 16 or 17 years old whose height did not reach the Kommandant’s shoulders. During the roll call, as the Kommandant walked around the prisoners, my father took off the coat he had and put it on the boy’s shoulders, and he and the person on the other side of this young man lifted him up so that he was tall enough to survive.

The most amazing story came in late 1967. My friend’s brother got engaged and we were invited to the kiddush the following Shabbos. We went to wish the families mazel tov. My friend’s father took my father to meet the kallah’s parents, Rabbi and Rebbetzin Gulewski. My friend’s father introduced my father as Duvid Roth. When Rabbi Gulewski heard the name he stared at my father for a few seconds, then threw his arms around my father and said to him in Yiddish “Duvid’l, az nit far eich vet mir nit zein duh heint.” Translated it means: Duvid’l, if it weren’t for you we would not be here today. I was not aware of this, as I was too busy drinking l’chaims with my friends. My father did not say a word about any of this when we got home. The wedding took place a few months later, and my parents were invited, not by my friend’s parents but by the kallah’s parents.

The rabbi who performed the ceremony was the uncle of the kallah, Rabbi Shmuel Schorr. When Rabbi Gulewski introduced my father to Rabbi Schorr he threw his arms around my father and cried. He too said that were it not for my father they would not be alive to celebrate this simcha. Rabbi Schorr made my father promise to come to Israel for Yom Ha’Atzmaut that year. My father could stay for as long as he wanted to as Rabbi Schorr’s guest. Soon after the wedding he announced to us that he was going to Israel after Pesach for three weeks, and would be staying with his friend Rabbi Schorr, in Givatayim, Israel. A couple of days after Pesach my father boarded an El Al flight to Israel. Communication in 1968 was nothing like it is today. In order to make a phone call you had to find a store that had a phone, and hopefully were able to get a line to the U.S. We hadn’t heard from my father for three weeks. When he arrived back home we asked him about his trip. He responded with a few shrugs, said he met some old friends, went to the “Koisel” and had a nice time. That was it.

About three weeks later we got an envelope from another friend’s parents who had recently made aliyah. The envelope contained three pictures of my father with various people. The letter explained that the pictures were taken at the melave malka that was given by my father’s friends in his honor, the night before he was to return to the U.S. There were more than 300 people who attended, all of whom said they owed their lives and survival to my father. When asked to explain, again my father just shrugged. After he developed his pictures of the trip we found one picture of my father on Har Herzl, taken on Yom HaZikaron, standing near President Zalman Shazar as he was laying the wreath at the grave of Theodore Herzl. We think that one of the people he saved was a member of the Knesset, and that he was able to arrange for my father to be there.

In 1991, when our son Moshe was a Senior at TABC, he decided to go on the March of the Living trip to Poland and Israel. The group was leaving to go to Poland a few days after Pesach and would spend a week in Poland visiting the various sites of the Shoah, and then go to Israel for Yom Ha’Atzmaut before returning to the U.S. Knowing that I and my sister knew very little of what my father had experienced during the Shoah, Moshe insisted that my father tell him everything “in order to prepare for his trip.” (My father used to spend every other Shabbos with us after my mother died.) Moshe sat with my father every Shabbos afternoon for hours, taking it all in. If my father heard me listening in the other room he would stop talking until I left. I now understood that in all the years my father was trying, in his own way, to protect us from learning about the evil that occured in Europe between 1939 and 1945.

It was then that I learned what my father did during the war that made him a hero to 300 people. When the war broke out he was living in Vilna. While in Kovno, the Nazis forced the Jews into a ghetto. The German army needed workers to help build and maintain an airfield outside of Kovno. My father, who was blonde and had blue eyes, also spoke German fluently. Because of these qualities, and his personality, he was able to curry favor with the Kommendant of the ghetto. He was allowed to join the workers who helped maintain the airfield outside the city. At the end of the day, as he returned to the ghetto, he was able to smuggle much-needed food into the ghetto, which he distributed to the residents. This was all done with the tacit knowledge of the Kommendant. This went on for several months, until the area Kommendant came and found out. My father was severely beaten, and, baruch Hashem, was spared because of his looks, and was sent to Dachau.

My father passed away in October 2000, at the age of 87, having experienced the joy of seeing four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. I know in the dark days after the war he could never imagine that he would live to see grandchildren, and certainly not great-grandchildren. We will never really know what he went through or what other heroic acts he was responsible for.

After the war, my father, as did many of the survivors, chose not to believe in God. Perhaps the establishment of the State of Israel, and the fact that he had two brothers and two nieces who survived, allowed him to understand that we as humans cannot understand God’s plans. Perhaps he felt that the Jewish people needed to repopulate and that religion was the way. Regardless of why, he chose to once again accept God and to observe the mitzvot. He realized that he was given a second chance, and lived every day to the fullest. May the zechut of the lives he saved be his legacy. Yehi zichro baruch—Dovid ben Shmuel Tzvi, the quiet hero.

By Rabbi Steven Roth