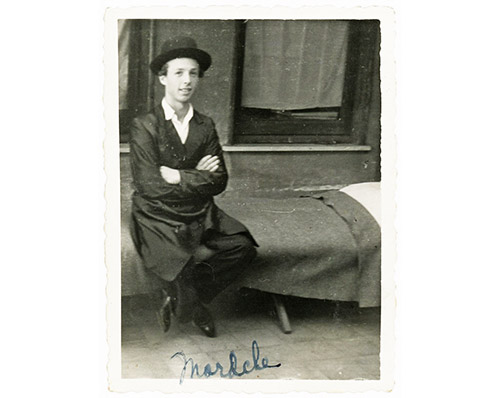

Mordechai Stern was a quiet man, with a deeply tragic personal history that he kept locked up deep inside him—though it was shared by many other European Jews. He was born into a family of Satmar chassidim, in the small town of Dej, Romania (later Hungary). As he later told it, life there was simple, mostly uneventful and wholesome … until it wasn’t. The Nazis only got around to invading this region in 1944, by which time their eventual defeat was pretty much inevitable—so they did their best murdering as many Jews as they could in the time left them. Mordechai was the only survivor of his family: He lost both parents, a baby brother, six sisters—one of them married with a baby—and almost all his friends and relatives.

All alone in an apathetic world, his community obliterated, Mordechai wanted to emigrate to Israel, but the British had by then scuttled that option. He instead ended up in North America, met and married my mother, and they settled in her hometown, Brooklyn, New York. As a young husband and father, he moved through a few jobs until he settled in running the machines in a knitting-mill—“honest work” for which he was vastly overqualified, for he possessed a formidable intellect and a phenomenal memory. His yeshiva education cut short at 14, and having never had any secular education at all, Mordechai ultimately spoke English at a college level (self-taught), knew Tanach and most, if not all of Shas, and was fairly well-read in secular material, too. But his immediate task was to provide for his growing family, and so he worked—12 hours a night, six days a week. Eventually he switched to working 12-hour days instead.

Mordechai Stern was a quiet man, unassuming in manner and appearance—though his posture and general bearing were unmistakably dignified. But he was iron-willed in his commitment to his parents’ values, principles and minhagim … and in general, to doing what was right. He was fierce in his support for the State of Israel and his rage at those who wished harm on his fellow Jews. He was largely free of vanity and never indulgent—but he found gentle pleasure in riding his bike alone for miles on end, and he took a measure of pride in his workout regimen at the gym, which he stuck to for very many years. He endured endless emotional agony at the thought of the unsaid goodbye to his whole family … but he was nothing less than mighty in how he marched on through life, one step at a time—even though, to someone like him, darkness was perpetually closing in on the periphery of his worldview.

Mordechai Stern’s general policy was to avoid trouble. Yet when the New York Times in 1994 published a nasty, antisemitic cartoon—what they call “political commentary”—which, he observed correctly, could’ve come from the pages of Nazi Germany’s Der Stürmer newspaper, he did not rationalize reasons to do nothing. This man in his mid-60s marched up and down, a moral army of one, holding a protest sign in front of the New York Times building in midtown Manhattan. He simply could not witness such a display of antisemitism and do nothing. He was not an activist by nature, but Mordechai Stern did what needed to be done.

Like many people whose whole families were brutally murdered while the world stood by, Mordechai was not very inclined to trust or empathize with non-Jews—a fairly reasonable outlook considering his personal experience (only the cluelessly arrogant argue that point with a Holocaust survivor). At least, that was the way he talked. But when, riding his bike along Brooklyn’s Belt Parkway near the Verrazano Bridge, he encountered a despondent young man threatening to “end it all,” he approached the guy and waited with him, telling him that things would get better, until help arrived. Of course he did: he did not have it in him to be cruel, or to shirk his duties as a decent, caring human being.

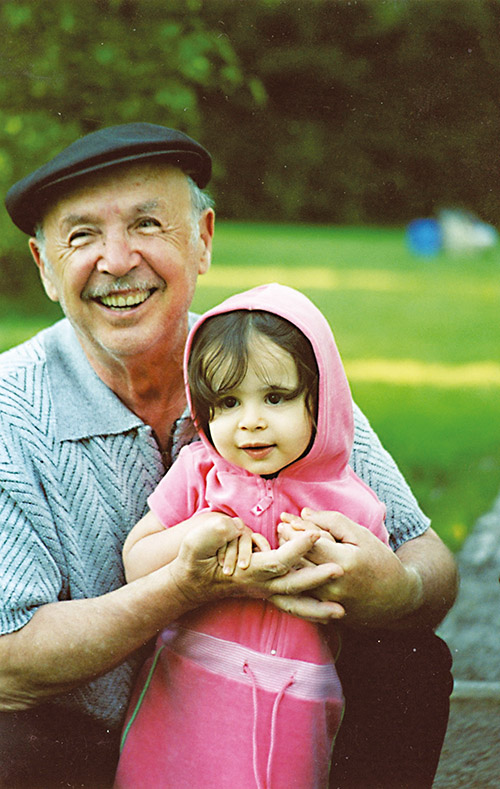

Mordechai—Uncle Mordche to younger family members—carried within him more grief than any person should, for the duration of his life. But my mother always lived by the principle that when life presents you with simcha, you don’t turn away from it. Nor would she allow him to live that way. So he played with, and loved, every one of his dozens of grand- and great-grandchildren. He went to every single family simcha. And he danced, and he smiled … and on a few very rare occasions, he spoke in honor of the event. At such times, friends and relatives caught a glimpse of this reticent man’s astonishing intellect, his command of Torah sources and his creative wit; his profound humanity, surprisingly modern broadmindedness and his unwavering values. Beneath it all, they sensed the ravaging loss that never stopped burning within him … and the bitachon that glowed in him at the same time.

When Mordechai Stern was niftar a few weeks ago, just short of his 93rd birthday, my brother, sister and I felt the intense loss of a loving father … but also, gratitude for having had our time with this righteous, reserved, deeply sad yet witty and quick to smile, gentle but incredibly strong man whose life was derailed at the very start—but who persevered even when he thought he could not, and who imparted to us so very many feelings, values and principles of how to live as a Jew and a mentch … all of which impel and guide us and our children always, in everything we do.

לע״נ מרדכי בן צבי יונתן

In loving memory of my father, Mordechai Stern.

Josh Stern lives with his family in Springfield, where he is working on a novel. He has his dad’s penchant for fixing stuff, doing what needs to be done and an aversion to melodrama. He did not inherit his father’s tendency to talk too little.