Allan Brauner began his vast project over five years ago. He readily admits it likely won’t be finished in his lifetime, although it won’t be for lack of trying.

Brauner, who lives with his wife, Margery, in Fair Lawn and attends Anshei Lubavitch, explained that when he took early retirement in March, 2012 as an IT director at a Fortune 50 company, he had a personal bucket list. Since then, one item on the list has overwhelmed all others.

He took The Jewish Link through the chronology of his project, which is actually more a mission. His mother, originally from Munkacz, Czechoslovakia, had been an Auschwitz survivor. She arrived there in 1944 at the age of 19 and was freed the following year when the war ended, although not before experiencing the brutal Death March at Ravensbruck, a women’s concentration camp. It was not until the year 2000 that she began to write vignettes about her wartime experiences.

Brauner explained that he was determined to compile those vignettes into a book for his family, and for his great-great-grandchildren down the road. He held his hands about 10 inches apart to illustrate the size of the stack of papers and the enormity of the job at hand. “Instead of playing golf or watching TV, I want to spend my retirement finding out what happened to my family, the town and people who no one remembers because they were erased by the Germans,” he reflected.

Brauner spoke of his mother’s recollections. “She remembered everything,” he said. He had fact checked her statements and found documents that verified her uncanny accuracy. Arriving in Auschwitz, she had been placed on a different line than her mother and brother. She repeatedly tried to join her mother, only to be rebuffed each time. Josef Mengele finally interceded, placing a riding crop between the two and saying “You will see your mother every Saturday.” She returned to her line, never to see either relative again. Other prisoners nearby, knowing what each line meant, matter-of-factly told her “The only way you’ll see your mother again is through the chimney.”

Alone, she was befriended by a younger girl named Margitka, who was 15 at the time. The girl followed her around and was cared for and brought food by her. They shared experiences throughout the course of their captivity.

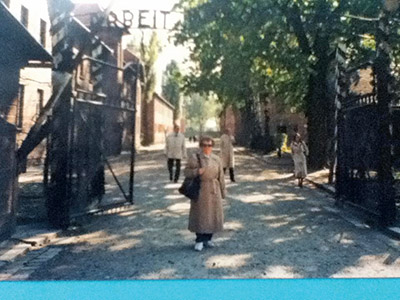

Fast forward to the year 2000. Writing the vignettes must have awoken something in Brauner’s mother. In June of that year she convinced her son to take her to visit Auschwitz. He reluctantly complied. He retrieved a picture of her standing near the front gate at the camp as if to say, “I won. I’m still here. You didn’t get me.”

Later that year, Brauner’s mother moved to an adult community in New Jersey. One day she saw a notice in the Jewish Press. Someone was trying to locate Toby from Munkacz from the 1940s era. She wasn’t sure if it was referring to her since there were others with that name, but contact was made. The person placing the notice was the daughter of Margitka. Margitka, aged 70 by then, and her daughters lived in Israel. The following year Brauner and his mother visited them.

Two months after his retirement in March, 2012, Brauner began his quest in earnest, with the interchange years earlier between his mother and Margitka likely one of the catalysts. He was told he could find archival documentation at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC. It is one of about a dozen such repositories throughout the world, with the originals in Bad Arolsen, Germany. This was to be the first of 15 visits Brauner paid to the museum. His zeal to learn more about his family soon expanded to include others who experienced the Nazi horrors but left no memories other than their names. He has since scoured a huge trove of national archives in Maryland, several pertinent locations in Manhattan, the International Tracing Service in Germany, and Yad Vashem in Israel. In addition, he has spoken with numerous archivists and historians about Nazi-era records.

During his initial DC visit, Brauner’s goal was to find anything related to his mother. He provided his mother’s name and the number on her arm, and the archivist went to work. Scrolling through the microfilm was a tedious job that involved much trial and error. Because prisoners were registered under different first names depending on the document, and because numbers found tattooed on the upper arm were sometimes reused, identification wasn’t simple.

After much searching, Brauner hit pay dirt. On an apparent time sheet with a chilling Auschwitz letterhead, a total of 228 women’s names and signatures were listed. One belonged to Brauner’s mother, another to her friend Margitka. The discovery, though, was more the beginning of a mystery than the satisfaction of an objective. The dates listed were November 8, 1944 to November 25, 1944, which Brauner surmised were a specific work period. There were four to five columns, starting with one that showed the tattooed ID numbers. Another included neatly written names clearly entered by the same person, followed by a column with prisoner signatures and another for “premiums.”

Brauner learned that the sign-in sheet was for work performed at the women’s prison tailor shop. It took him over a year of speculation to conclude that the premiums were coupons, ostensibly to buy items at the Auschwitz “canteen.” He doubted a canteen even existed at that camp. The premium column was more likely a ruse to hasten the sign-in process for administrative purposes.

Brauner considered this to be a case study of how to piece together information to flesh out a story. He has begun tracking down the history behind those names and girls’ ultimate fates. Many did not survive the war. “I’m doing it,” he said, “because each girl deserves a memory.”

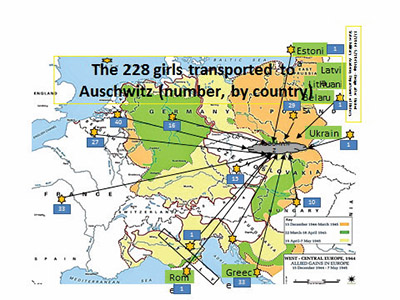

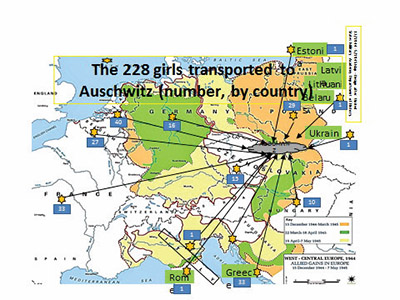

He has learned that the 228 names belonged to girls from 14 different countries, most of whom had been in their early 20s. He also discovered that prisoner numbers were sequenced by where the person was from and when he/she was brought to a camp. The number alone could therefore go a long way towards pinpointing its owner’s identity and background.

Brauner has been told that there are about 100 million Nazi-era documents involving 15 million individuals. He spoke with top scientists regarding the daunting task of physically gathering all the documents and scans from various locations, then translating and transcribing them so they can be available in one huge repository. He was told it would be impossible. Undeterred, Brauner told The Jewish Link “I’ll do it anyway.”

Given his long career working with massive backend databases, he just may be able to make good on his quest. He spoke of conversations he’s had with tech people at Google, Amazon and Microsoft. His dream is to have artificial intelligence help in the process—think IBM’s Watson—and not only fill in the blanks but make each individual’s story come alive. He quickly ticked off ideas. “You could scan all the pages with Google Glass, drop them into a database and have Watson read them and learn them, and be able to tell the story. Here’s a picture, here are some facts, and Watson does 60 percent or 70 percent of it, while humans do the rest. He continued, “You could ask a question, like what’s your name and that number on your arm, and you are transported into a virtual reality environment as an avatar talks to you and the real story of those people and what each has experienced comes to life.”

To an extent, some of this is already happening at Yad Vashem and other Holocaust memorials, but Brauner wants to take it to another level. The first step is to sift through and aggregate all the known data from the people who lived through the Holocaust. So much is out there if we can effectively gather it. This would be followed by employing the latest technologies in this arena. Using the avatar example, “We can put ourselves into a virtual environment and virtually experience what they experienced living in these death camps, as well as their lives before and after. In essence, these people would be coming back to life for anyone to see.” It’s akin to Ancestry.com on steroids, not just knowing the history but stepping into it.

In an understatement, Brauner added that “It’s so much more compelling than a book.” Given all the forces vying for our attention these days, Brauner’s vision makes a whole lot of sense.

By Robert Isler

Robert Isler is a marketing researcher and a senior content writer who lives in Fair Lawn. He can be reached at robertisler23@gmail.com.