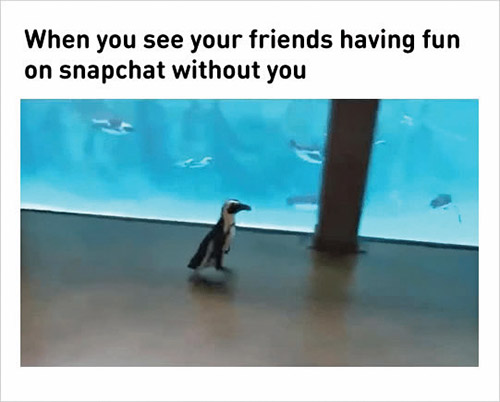

Summer can engender false perceptions of fun. Although I don’t use social media, many friends confide that they always feel inferior after checking other friends’ WhatsApp, Snapchat or Instagram status pictures because their fun seems “funner.”

Perhaps someone posts a photo of herself in sunglasses. Where is she? On a perfectly populated Florida beach with another friend, who lives in Orlando. She went to Disney World yesterday. My friends see the post and think: “When we went during mid-winter vacation, we didn’t have that ‘magical’ experience. Maybe we didn’t ‘do’ Disney World right. We didn’t ‘do’ fun right. Maybe we’re not ‘doing’ summer right.”

The summer is now beset with a teenage version of “mom-shaming,” when moms inadvertently bash the habits of other moms through bragging blogs and Facebook posts. Similarly, our summer activities just don’t seem exciting enough compared to our friends’; I like to call it “summer shaming.”

School’s out, so my friends and I feel like we’re supposed to be doing everything we should do when there is no school. And what do we do with no school? We try to have fun. So we ask ourselves, “Am I having fun?” If the answer is “Let me post this picture to validate that ‘I’m having fun,’” then, ironically, no, we’re not. Subconscious plan B is to instinctively engage in a social forum as a means of attaching ourselves to this “fun.” We believe social media validates us by validating the choices we make to have summer fun reach its utmost potential. It is this validation that PNAS, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, defines as “the process of determining the degree to which a model is an accurate representation of the real world from the perspective of its intended users,” that determines the success of our summer.

This quasi-existential summer crisis originates in the pressure to rejuvenate from the previous school-term stresses. We are determined that fun will serve as that much-needed relief factor. John Kehoe, author of “The Practice of Happiness,” explains that “fun increases our flow and intake of energy, and when our energy is at a high level we function better.” But we want to believe that fun comes from the posting validation, when, in truth, the fun induces the validation, as Kehoe writes: “Having fun daily, even if it’s only for a few minutes, is a life-affirming practice. It’s also a powerful symbol to our subconscious. It is saying I am worthy. Life is good.”

The real problem, however, is that these “photos of fun” aren’t just fooling the poster, but are coming down even harder on the recipients. Beverly D. Flaxington, author of many personal- and professional-development books, elaborates, “By constantly comparing themselves to apparently perfect images online, social media users whose self-confidence is lacking can become more anxious or depressed over what others seem to have and they don’t. That nagging feeling of not being able to measure up will only lead to less self-confidence and an erosion of self-worth. Each log-in can chip away just a bit more of any good feeling a person might have had.” This inferiority complex dominoes until the “checkers” are consumed with the same insecurities the poster originally had, pressuring the former to rejuvenate better, to have fun better, consequently restarting the vicious cycle.

These comparison-induced self-doubts are nothing but monsters in our head, egged on by the scariest teenage FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) tyrant of all. David Lopera, a neuropsychologist published in Innovation, Princeton’s journal of science and technology, defines FOMO as a form of loss aversion: “The tendency for people to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring gains. In other words, people may be incentivized to go out for the sake of not missing out and avoiding the regret, rather than for the act of going out in and of itself…The automatic assumption is that everyone else is out having a good time and we are not.” And, because we are not there to experience it in reality, we inexorably imagine the posters’ lives as “better,” “funner,” when the picture very well could have been a facade. Hui-Tzu Grace Chou and Nicholos Edge, authors in the Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking journal, indicated “that those who have used Facebook longer agreed more that others were happier, and agreed less that life is fair, and those spending more time on Facebook each week agreed more that others were happier and had better lives.” What’s worse is that FOMO negates any prior rejuvenating fun enjoyed before checking WhatsApp, Snapchat, Instagram or Facebook. As Lopera succinctly sums up, “Conformity, along with loss aversion, induces negative feelings.”

These “negative feelings” make us forget what’s truly fun, what summer is really supposed to be. Sometimes, that rejuvenating moment when summer finally starts to kick in is having that thousand-calorie ice-cream you pretended to earn at the gym. That is real “summer fun.” Summer is not a competition. So remember, fun may lead to validation, but you should not require validation to have fun.

By Rachel Liebling

Rachel Liebling is a summer intern at the Jewish Link and a rising freshman at Stern College for Women.