When Zac Levy encountered a homeless young woman, he remembered the “60 second rule” his father taught him: when you have an idea or thought, act on it immediately.

He applied that rule after the encounter two years ago when the then-16-year-old was waiting in line at a 7-Eleven with his father in the Boston area. Suddenly the woman “came out of nowhere and slammed down a drink” and then began fumbling for change to pay for it. Watching her search, his father paid for the beverage and she walked out. After leaving the store they noticed her on the side of the road with her meager belongings and realized she was homeless. Levy felt both compassion and curiosity about how someone that young — he estimated her to be about 18 or 19 — got in that position.

“As soon as I got home I started doing some research and reading articles trying to find out what causes homelessness,” said Levy, a resident of Deal, New Jersey. “I kept coming back to the same conclusion that the straw that broke the camel’s back was losing a job, mental illness or drug addiction, but no one was really talking about what came before that so I started trying to figure out the chronology.”

Unable to find an answer online, he started contacting homeless shelters, soup kitchens and organizations throughout Monmouth County, interviewing leaders and clients. He found that many homeless people had traumatic backstories, including horribly abusive childhoods, that deprived them of coping skills that led to their predicament.

“The stories I heard shocked me,” said Levy. “These people had some sort of prior experience in their past that if I had the same experience I don’t think I would be able to break out of it.”

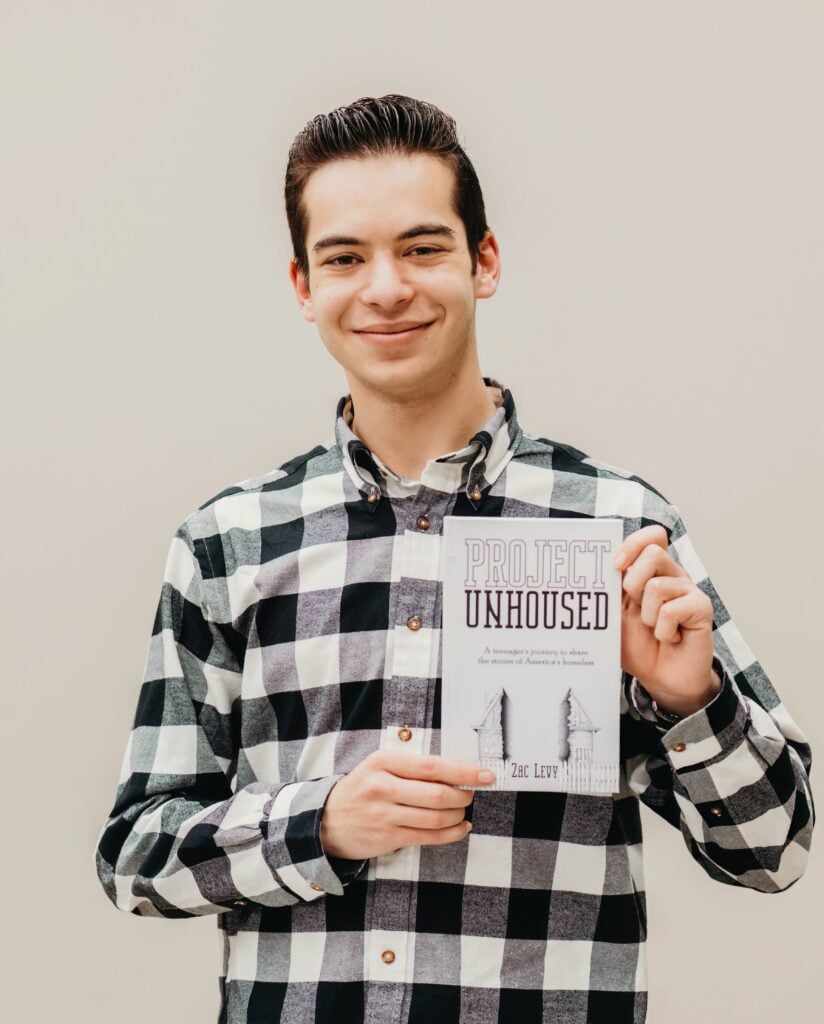

All of Levy’s research resulted in his founding a homelessness prevention initiative, Project Unhoused, with the goal of spreading awareness about and aid for America’s homeless population. Through the organization Levy has raised $10,000; run various initiatives, including winter clothing drives and a GoFundMe campaign; and has written a book, also called “Project Unhoused,” the profits from which are earmarked for the homeless. The book documents the dangers behind many popular misconceptions about homelessness.

“I wanted to spread awareness and also spread knowledge about the power of the individual,” said Levy. “Treating [the homeless] with dignity and compassion can definitely make a major difference.”

That desire to help others is deeply rooted in Levy’s religious upbringing among Deal’s large Orthodox Syrian community. He attended Hillel Yeshiva in Ocean Township, but later went to High Technology High School, a public school offering a rigorous pre-engineering curriculum located on the campus of Brookdale Community College in Lincroft. He is also a graduate of the Rutgers University quarknet program in particle physics and quantum computing and has been working in labs at Princeton University conducting research in neuroscience and biophysics, where Levy will be majoring in physics this fall.

However, he has continued daily Torah study with his rabbis and views his work as a Kiddush Hashem.

“We learn about the importance of chesed and giving back,” said Levy, whose book was published Oct. 5, just two days before the terrorist attack on Israel by Hamas and the war that unleashed a torrent of antisemitism.

“I interact with lots of people and organizations outside the Jewish world,” said Levy, who also has had many speaking engagements. “I always wear a kippah and it allows me to put a positive step forward for the Jewish community.”

Levy has worked with leaders of local nonprofit organizations in the Monmouth County area, including Interfaith Neighbors, the Bradley Beach Food Pantry, Lunch Break, Jersey Shore Rescue Mission and the Winifred Canright House. In addition to everything else, he found there is a critical shortage of low income housing and an enormous amount of energy is required to even get on a long waiting list.

One of the people he wrote about in his book was James, who was in his mid-40s and whose history was typical of many Levy encountered. He grew up in a middle class family and attended an expensive Catholic school, but his father worked long hours, was rarely home and when he was he was often drunk and abusive, while his mother suffered from agoraphobia and rarely strayed too far from home. They divorced and his father left, leaving few assets for his family and James unable to afford college.

Yet, James was able to move on with his life finding employment in a fast food restaurant, starting a YouTube channel and dating. Then in his mid-30s he was mugged and his jaw badly shattered, leaving James bedridden and unable to work for months and in excruciating pain, for which he was prescribed morphine. On top of that, during this same period his younger brother was killed in a car accident.

“He always blamed himself because he was supposed to be driving, and [he] became extremely depressed,” said Levy, adding that the final blow came not long after in 2012 when Superstorm Sandy flooded many shore communities and James and his mother lost their apartment. Still in emotional and physical pain, someone introduced James to heroin.

“If he grew up in a normal household he’d be able to cope better,” said Levy. “But when he suffered a first blow, then a second and a third he just didn’t have the normal coping skills to deal with it. My main point is that the homeless problem isn’t just a problem of mental health or drug addiction. Researchers would diagnose the problem as drugs, when really it was everything that happened beforehand.”

As part of his efforts Levy has conducted nine clothing drives, setting up in parking lots in Asbury Park to give out clothing, blankets and pillows; is working with wholesalers to provide items he has learned are the most essential and useful for the homeless; and has begun providing a monthly stipend to some of those he met for his book research. His latest initiative is a watch drive run in partnership with the Belmar Public Library.

“Someone told me when he loses his watch or his phone, if he even has a phone, he has no idea what time it is if he’s out on the street,” said Levy. “So many organizations have specific times where they give out food and if you’re not there in that hour you don’t get food. Some have a small job and need to get there on time.”

Levy said the previous week he gave out 50 watches and repaired another 80-100. “Also, a major thing with this is dignity, to have something that is yours, a possession,” he noted. “Out on the streets you have to hide things away. If you have them in a backpack they can be stolen while you’re sleeping but no one is going to steal a watch off your wrist. It is a major possession that is yours.”

If nothing else, Levy hopes people will come to view the homeless as people struggling to survive and treat them with dignity.

“If they had a rough day these people still need to figure out where they’re going to sleep,” he explained. “When you pass someone on the street, just giving them a smile or saying hello can really go a long way.”

The book is available on Amazon and contributions can be made through his website, projectunhoused.com.

Debra Rubin has had a long career in journalism writing for secular weekly and daily newspapers and Jewish publications. She most recently served as Middlesex/Monmouth bureau chief for the New Jersey Jewish News. She also worked with the media at several nonprofits, including serving as assistant public relations director of HIAS and assistant director of media relations at Yeshiva University.