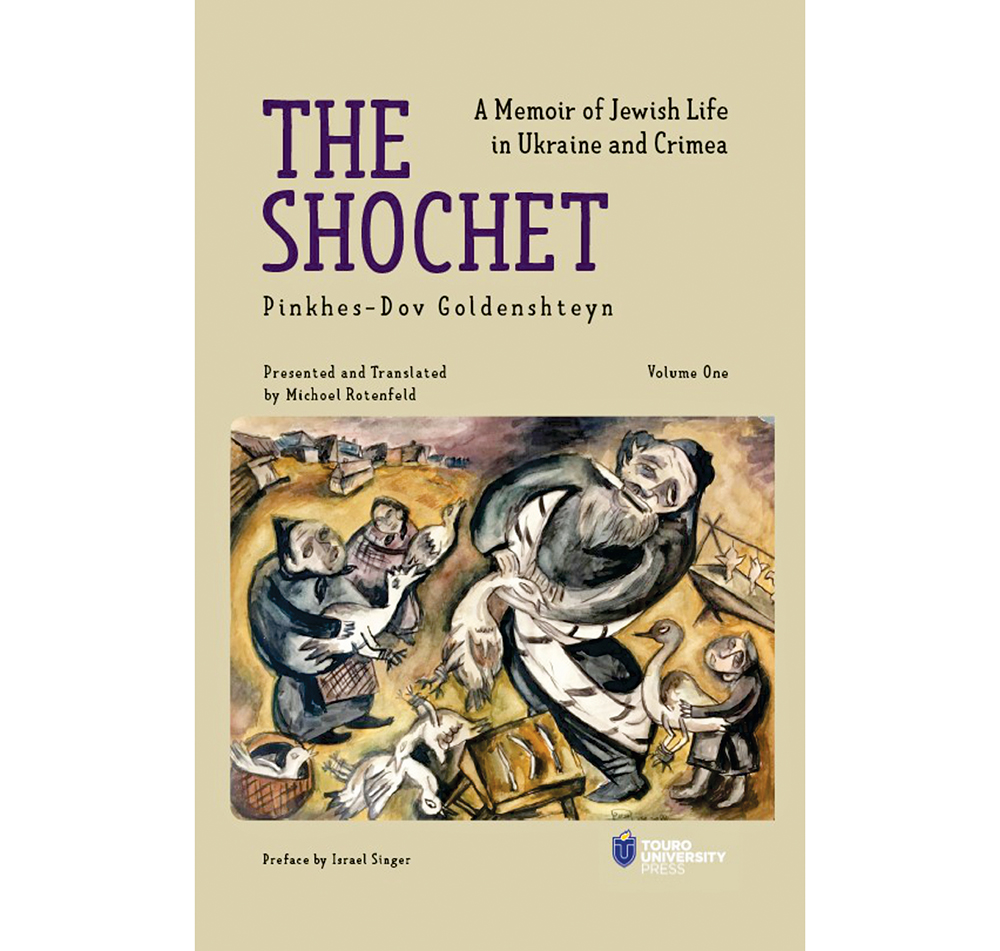

Reviewing: “The Shochet: A Memoir of Jewish Life in Ukraine and Crimea, Volume I.” Paperback. By Pinkhes-Dov Goldenshteyn (Author), Michoel Rotenfeld (Translator); Touro University Press, September 2023.

“The Shochet” is an innocuously titled travelogue memoir of a righteous, forward moving, determined individual who recorded his difficult life in the later years of the 19th century and the early parts of the 20th century. In this masterpiece of detail, much peril and danger is presented and discussed, including the fright of border crossings, the terror of poverty and oppression, the nastiness of underhanded charlatans, and the inhumane snobbery of class warfare. The subtitle — “A Memoir of Jewish Life in Ukraine and Crimea” — is also plain and unassuming, with slight hints to the peripatetic nature of the story but barely a hint of the cauldron of difficulties this gentleman had to pass through.

Pinkhes-Dov Goldenshteyen’s unimaginable suffering, jump-started by orphanhood, is so thematically similar to Charles Dickens’ “David Copperfield,” that this chronicle of terrible human agony might as well have started with the famous “I am born.”

That’s how much of a steel-trap memory the author displays in telling his life story of wretchedness and affliction. What’s noteworthy about this gift of memory is that everything he tells is backed up by historical research save for one little thing: he never knows what year it is, and can’t figure out how old anyone is, including himself. What is up with that? Well, the introduction — fully one-fourth of the entire book — tries to explain this phenomenon, but the book is still wonder worthy. You can look all of this up and everything lines up. The translator takes very good care to plot all events properly and linearly, lending credibility to the narrative despite this quirk on the original author’s part. The details of the story do seem to hold up to history’s microscope.

The introduction — by the capable hand of the talented translator from the original Yiddish, who spends lots of time in footnotes filling gaps, explaining ritual, uncovering historical information, and showcasing his extensive research — expends much ink in explaining how rare a telling this story is, and compares it with other valuable and notable works of literature that mine the same territory. This too, seems to be so. The story is sui generis (in a class by itself), especially for the era and the personality and the location, but we now have to talk about all this terrible anguish.

The entire narrative urges the astute reader to ask why he suffers so much. The author has unimaginable faith and undaunted drive, but it doesn’t seem to get him anywhere. His life is like an accounting bank-o-meter that keeps track of his wealth as it goes up and down from 0 to 30 rubles or thereabouts. He’s a jack of all trades, master of some, and can’t make a sustained living. Why?

Those are just economic concerns. As for the story itself and the physical torments the author is forced to undergo, I could steal every word in the thesaurus under “suffering” and it still wouldn’t explain just how much suffering he’s made to endure and why he seems to suffer so much. Did the Satan of the Job story pick Pinye-Ber as his next project? Did the author leave something unrevealed about his miserable luck? Did the fact of his undying faith in God mean that he farmed out too much responsibility to fate itself? Could no one advise him on prudent paths to a decent livelihood? Was he too headstrong? What is it exactly? Why did the Shochet not know or say?

The details of what the author endures are mind-blowing, and the author and the translator guide the reader to why our hero perpetually finds himself in certain situations that can be explained by changes in law, jurisdiction and historical context, but does not discuss these at all. The introduction also spends a lot of time explaining why this lack makes this a more pure telling of a personal history. I surmise the possibility that the author wished for his heirs to discover these higher power reasons for themselves. Why does he find himself in certain situations? Why does he not find himself in better situations? Why? What is happening around him? Pinkhes-Dov, we can’t stand to see you suffer so.

Finally, one more question is prompted. It is clear from the author himself, and expounded on in the introduction, that the purpose of recording this life history is to inspire his children to remain fast to the path of faith. If so, I must ask what the author himself asks early on in his autobiography, quoting Moses our teacher: “This is Torah, and this is its reward?”

Maybe “The Shochet, Part 2” will answer this question and all of the above.

To order “The Shochet: A Memoir of Jewish Life in Ukraine and Crimea: Volume I” on Academic Studies Press, visit www.academicstudiespress.com/9798887193557.

It can also be found on Amazon.

Martin Bodek is the author of 12 books, including Zaidy’s War, a biography of his grandfather’s service and survival in Europe having served in four armies. He is also the author of The Jewish Link’s weekly beloved “Cuff Link” column. His fifth parody haggadah, “This Haggadah is the Way: A Star Wars Unofficial Passover Parody,” just launched. Reach out to him for book talk opportunities at martinbodekbooks@gmail.com.